|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

|

|

The older you get, the humbler you get. I know I don’t have that much to offer, and I know I’ve now read Moby Dick and Anna Karenina, and if I had read those books before I wrote The Hottest State, I don’t think I’d have published it. I had the arrogance of the uneducated, which sometimes you need.Ethan Hawke

Why, you may ask, is this column about Ethan Hawke’s writing? Does anyone think “writer” first and “actor” second when they think of Ethan Hawke? To put a local spin on it, I suppose I could say that Hawke’s Princeton-area roots are my main excuse for spending a column on two books that didn’t have enough literary clout to put him on hot young writer lists like the New Yorker’s “20 Under 40.” Anyway, he’ll be out of the running for that list this November 6 when he turns 40. But why bother with his prose? Why not focus on Dead Poets Society, Reality Bites, A Midnight Clear, and the other films that put him on the map and enabled him to score a fat advance for his first novel?

The answer to all these questions is, in fact, a film, Before Sunrise, which was the subject of an earlier review (Town Topics August 4), along with Before Sunset, in which Hawke plays Jesse, a first-time novelist who re-encounters the love of his life on a book tour. The actor had been on a few book tours himself by then, having published The Hottest State (Little Brown) in 1996 and Ash Wednesday (Knopf/Vintage Contemporaries) in 2002. The fictional fiction that brought him to Paris in Before Sunset was based on his first encounter with Julie Delpy’s Celine in Before Sunrise.

In the course of online research when I was writing the Sunrise/Sunset column, I found some interviews with Hawke that made me want to at least have a look at the novels. His self-deprecating reference to the subject matter, “romantic love,” or “boy-girl” stuff, suggested it might be interesting to compare the way he handled that particular dynamic on the page. I figured that the dialogue had to be good or that it at least might contain interesting echoes of the dialogue in Before Sunset, where the actors were, in effect, writing their own parts (Hawke and Julie Delpy were jointly nominated, along with Director Richard Linklater and writer Kim Krizan, for a Academy Award for the Best Adapted Screenplay).

When I took up The Hottest State, my plan was to read around in it, just to get a taste of its quality, but I found myself reading it through, drawn back to it, even though I had no intention of finishing the book. And this is not your typical page-turner. The plot is about as basic as it gets: boy meets girl, boy falls in love, boy loses girl, boy falls apart. If this sequence sounds familiar, no wonder: it’s echoed in a thousand my-girlfriend-dumped me rock songs.

So what happened? Why did I stay with Hawke when I’ve given up on most best-sellers I’ve sampled (with the exception of Stieg Larsson’s) and have frequently lost patience with acclaimed works by “serious writers” like Jonathan Franzen, David Wallace, Dave Eggers, and Jonathan Safran Foer? It’s not like I shy away from a tough read. I’ve read and enjoyed four mammoth literary blockbusters in the past few years, Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, Alexander Theroux’s Laura Warholic, and Roberto Bolano’s Savage Detectives and 2666. It helped that Hawke didn’t flex his stylistic muscles. No fancy footwork, no copious, narrative-busting footnotes, no cute displacements of time, space, and persona. Just boy-girl stuff, but taken to another level.

Setting the Course

As I expected, Hawke writes excellent dialogue. Clearly he learned something from, or at least was impacted by, his work on the famously conversational Before Sunrise, which came out a year before the book. But The Hottest State is much more than a screenplay disguised as a novel (though a movie version did come out in 2007). Mainly, it passes the truest test: the two main characters come to life. You understand almost from the first moment why William would love Sarah and why Sarah would eventually dump William.

The first time you see Sarah is after William introduces himself to her:

“She didn’t say anything. She just smiled and looked down. She was quiet. Her whole body — her eyes, her breasts, her arms placed neatly in her lap — was quiet. Only her hair stood out, undisciplined curls of black that seemed to belong to someone else. Her skin was unusually white and her nose appeared to have been misplaced on her face. I guess she would be called funny-looking.”

At this point, William swings into a rap not unlike the sort Jesse regaled Celine with in Before Sunrise. Quoting Spock in Star Trek (“that episode where he tells the replicants that everything he says is a lie”), he tries to cover himself by saying, “See, you seem a little stiff to me, and I’m trying to make sure you’re not a replicant,” to which Sarah says, “You’re weird.”

Thus begins an exchange that offers evidence of what Hawke does with dialogue:

“‘Yeah, yeah, I am,’ I said. ‘But you’re finding yourself oddly attracted to me, aren’t you?’

“She looked at me.

‘You have nice teeth,’ she said. “Nice crooked teeth.’

‘Thanks.’

‘You have the strangest energy,’ she said. I remember that exactly.

‘Energy?’ I said. ‘I didn’t know we were going to be using words like “energy.” And when did I put myself up for your judgment?’

‘I don’t know. You just seem to require a lot of attention.’”

By the end of the conversation, William is in love. What hooks him is that she isn’t conventionally attractive (nor conventionally easy to figure out, same idea) and that she seems to see through him. In their first back and forth, you have a microcosm of the relationship, its birth, its trajectory, and its death. When Sarah can no longer deal with William’s energy and need for attention, she rejects him and he has a 20-something tantrum.

Mad Love

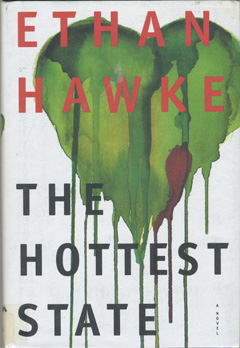

Though Hawke grew up around here and graduated from the Hun School, he was born in Texas, which is deeper in the heart of both novels than New Jersey. The title refers to a poem William wrote at age 7, which begins “Fort Worth is the hottest state I know.” Given that William comes perilously close to self-destructing when Sarah shuts him out, “the hottest state” also refers to l’amour fou. William is a love-crazed extremist. He breaks things, cuts himself, and shouts Romeo’s balcony-scene speech at the top of his lungs in the middle of the night on the street outside Sarah’s window. Her parting gift to him (on the occasion of his twenty-first birthday), which is replicated on the book jacket, is her painting “of a bleeding heart, done in eight thousand shades of green, with one spill of red that dripped down onto the frame.”

It’s obvious that Hawke has read and absorbed The Catcher in the Rye, but contrary to one negative review, you never feel that he’s consciously playing Holden Caulfield. He was also clearly influenced by the experience of working with Julie Delpy and Richard Linklater. One example: in Before Sunrise, Jesse and Celine project their feelings for one another in the form of make believe telephone conversations. In The Hottest State, William and Sarah improvise a dialogue on (appropriately enough) their imagined break-up.

Thanks to the stigma of being a Generation X movie actor, Hawke received some predictably cursory, patronizing, simple-minded reviews, the subtext being that he was a privileged character who would never have found a publisher had he been an unknown quantity. Reviewers who didn’t want to be bothered with a 196-page book by a young movie star could brush it off, as Kirkus does, with demeaning (and dated) references to the novel being geared to satisfy “teeny-bopper fans.” If you give his fiction a chance, you’ll see that Hawke happens to be an actor who was born to write.

The Writer Emergent

When I picked up Hawke’s second novel, Ash Wednesday, the same thing happened. I planned to dip into it and ended up reading it through. Although it may fit even more solidly into the boy-girl genre, with its exploration of the relationship between Jimmy and Christy, there’s an additional depth of contrast in the way Hawke uses alternating chapters that balance Jimmy’s visceral, explosive style with Christy’s comparatively stable, nuanced point of view. Driven by a street-tough confidence that the first book lacked, Ash Wednesday takes more chances, the words fly more freely, the full-blooded physicality evident in The Hottest State is more effectively managed, and the narrative has a passion and energy that puts the lie to the notion that writing is something Hawkes does when he’s not acting. My guess is that when he publishes his third novel, the writer will fully emerge from the actor’s shadow.