|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 34

|

|

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 34

|

|

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

|

|

In Philip Roth’s 1986 tour de force, The Counterlife, the author’s most durable fictional stand-in, Nathan Zuckerman, travels to Israel in pursuit of his brother Henry, who has morphed from a dentist into a gun-toting Zionist. Like Lambert Strether in Henry James’s The Ambassadors, Nathan imagines himself on a moral rescue mission, except that the femme fatale is Judea. His ears still ringing with the ingenious polemics of a Zionist named Lippman, he puts things in perspective by citing his and Henry’s New Jersey roots: “The fact remains that in our family the collective memory doesn’t go back to the Golden Calf and the Burning Bush, but to ‘Duffy’s Tavern’ and ‘Can You Top This?’ Maybe the Jews begin with Judea, but Henry never did and never will. He begins with WJZ and WOR, with double features at the Roosevelt on Saturday afternoons and Sunday doubleheaders at Ruppert Stadium watching the Newark Bears.”

In all the Roth I’d read up to that point, no one passage had spoken to me quite the way that one did. Though I grew up a generation later, a WASP from the midwest, my roots are in radio programs and baseball, the glowing dial and the boyhood diamond, my heritage rooted in that same realm where American ball players and entertainers were the original messiahs. Suddenly it made sense that the titles of three of Roth’s novels put America up front: The Great American Novel from 1973 (a whole book highlighting the national pastime), American Pastoral (1997), and The Plot Against America (2004).

According to The Facts (1987), his most unambiguously autobiographical work along with Patrimony (1991), Roth emerged from a medical and psychic crisis in the spring of 1987 “to focus virtually all my waking attention on worlds from which I had lived at a distance for decades — remembering where I had started out from and how it had all begun,” going back to “the boy … on the playground,” and “back to the original well, not for material but for the launch, the relaunch — out of fuel, back to tank up on magic blood.” If “magic blood” sounds a bit over the top, the phrase will make sense to anyone reading Operation Shylock (1993), which picks up where The Counterlife leaves off.

Aimez-vous Roth?

“What do you think of Philip Roth?” I recently asked a friend who had been struggling with his Jewish identity during the period when I knew him best. After telling me that he’d long ago outgrown his “Jewish angst,” he said that while he’d enjoyed and admired the five novels that he’d read, Roth’s characters and their dilemmas had “never resonated” with him.

In my five-month, ten-book whirlwind tour of Roth World, from his latest, Exit Ghost (2007), back to November 29, 1958, the date of the first piece he ever published in The New Yorker, nothing truly “resonated” until I got to The Counterlife. Reading and rereading him with something of a show-me attitude because he’s the only living novelist of his generation to be represented in The Library of America, I admired the intelligence and restraint in the books I reread, Goodbye Columbus (1959) and The Ghost Writer (1979), which everyone who reads Exit Ghost will be tempted to go back to, if only to compare the first and reportedly last incarnations of Zuckerman, and even more to return to young Amy Bellette after meeting the ailing old woman who comes into Zuckerman’s life again in a Manhattan cafeteria. Rereading Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), I admired Roth’s audacity as much as I did the first time. You can appreciate what he accomplished all the more if you read about his traumatic first marriage in The Facts, which also documents the abuse he was subjected to because of his devastating portrait of some Jewish soldiers in his New Yorker story “Defender of the Faith.” Portnoy was a Molotov cocktail intended to blow up in the faces of all the real-life defenders of the faith who attacked him because of that story.

Riding a Rush

In spite of a problematic epilogue and an allegedly missing last chapter, Operation Shylock, which I’ve just finished, is not only still “resonating” with me but ringing bells, clashing cymbals, honking horns, and setting off fireworks. The author calls the book A Confession, only to take it back in a note at the end (“This confession is false”). But then Roth is a consummate trickster (as he showed in The Counterlife, admitting in an interview: “Normally there is a contract between the author and the reader that only gets torn up at the end of the book. In this book the contract gets torn up at the end of each chapter”). It’s not enough to say Operation Shylock picks up where The Counterlife leaves off; the earlier book is to the later one as a rocket launcher is to a rocket. If anything, this would seem to be the most potent manifestation of the “relaunch” mentioned in The Facts. Roth is in Israel again, not in the guise of Zuckerman this time but under his own name, and he’s there not to bring back a brother but to confront a character who is going around claiming to be Philip Roth.

In Shylock, Roth’s magic mojo is working overtime. There’s no sign of strain, or civil restraint, and no room for the labored efforts to reproduce the speech patterns of a genteel (and gentile) Englishwoman, which became a chore to read at times in The Counterlife and even more in Deception. When Roth is going full-throttle, riding a rush, he sometimes seems to be in touch with the same comic muse Joseph Heller ravished in Catch-22, but he transcends the absurd even more powerfully than he does in The Counterlife by going back to Newark again. In a memorable encounter during which he’s listening to the life story of the sublime and ultimately irresistible Jinx Possesski, the faux Philip Roth’s delightful lover, the real Roth is thinking to himself that he should never have left “the front stoop on Leslie Street in Newark” back when “what was outside was outside and what was inside was inside, when everything still divided cleanly and nothing happened that couldn’t be explained,” which leads to this gem: “I left the front stoop on Leslie Street, ate of the fruit of the tree of fiction, and nothing, neither reality nor myself, had been the same since.”

Fifteen pages later, still tête-à-tête with Jinx, Roth provides another revealing glimpse of his creative origins: “In the face of a story, any story, I sit captivated. Either I am listening to them or I am telling them. Everything originates there.”

But the best is yet to come. Given the constraints of space, I’m not going to attempt to describe the wild doings in Operation Shylock, which would be like trying to explain the plot of The Big Sleep. In one extended, bravura sequence that includes a stunning account of Roth’s discovery of the alphabet at age five, there’s a passage that has to be among the loveliest and most resonant in his work. After being caught up in a demonstration outside the courtroom where John Demjanjuk (Ivan the Terrible) is on trial, Roth is abducted and imprisoned in an empty Jerusalem schoolroom by unknown forces. As he’s sitting on one of those “movable molded-plastic student chairs” trying to figure out why he’s there and who he’s waiting for and what fate has in store, he finds the schoolroom setting taking him back back to his Newark boyhood again. After admitting that the nine words written in Hebrew on the blackboard make no sense to him in spite of three years of afternoon classes at the Hebrew school (on top of six and a half hours of public school), he remembers how “we sat there and learned to write backwards, to write as though the sun rose in the west and the leaves fell in the spring, as though Canada lay to the south, Mexico to the north,” after which “we escaped back into our cozy American world, aligned just the other way around, where all that was plausible, recognizable, predictable, reasonable, intelligible, and useful unfolded its meaning to us from left to right.”

As if the beauty of this insight isn’t already enough, baseball crystallizes it when he realizes that the only place where “we proceeded in reverse, where it was natural, logical, in the very nature of things, the singular and unchallengeable exception, was on the sandlot diamond. In the early 1940s, reading and writing from right to left made about as much sense to me as belting the ball over the outfielder’s head and expecting to be credited with a triple for running from third to second to first.”

Again, here’s conclusive evidence in case anyone doubts the centrality of the national pastime to Roth’s life story (“Safe at Home” is the title he gave the first chapter of The Facts), not to mention the centrality of Newark, which is as close to the heart of his work as Hannibal, Missouri, is to Mark Twain’s, or Asheville, North Carolina, to Thomas Wolfe’s. In 2005 a street sign in Roth’s name was unveiled on the corner of Summit and Keer Avenues where he lived for much of his childhood; a plaque on the house where the Roths lived was also unveiled.

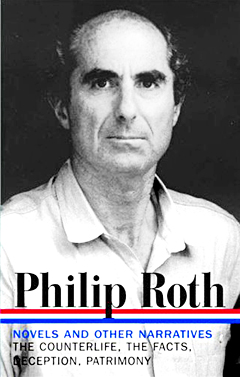

The Counterlife, The Facts, Deception, and the memoir, Patrimony, are contained in the newest volume in the Library of America’s Philip Roth: Novels and Other Narratives 1986-1991, which will be published September 4. His latest novel, Indignation, is also due out next month. Philip Roth’s 75th birthday was this past March