|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 49

|

|

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 49

|

|

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

|

|

It’s a lovely sunny summer’s day in Delft. You’re one among a group of American college students on a tour enjoying the high of your first hour in a foreign land. You’ve just come out of Vermeer’s house, still under the spell that began the night before, sleepless with excitement as the Dutch student ship Groote Beer moved through a thick fog, fog horns mooing, the hazy stuff of mystery, the veritable embodiment of foreign intrigue. The dock scenes and streets of Rotterdam, the Dutch countryside, Delft itself, everything shines like a vision, exactly the dream of another country you might have dreamed during some negative epiphany at a Stewart’s Root Beer stand in darkest dullest southern Indiana. You don’t feel merely an ocean away from the U.S.A., you feel a world away, nay, two or three centuries away, which is surely just as it should be in “the Old Country.”

Then, as you wander in your European entrancement through a street fair near a quaint park with swans, there comes a mad, barbaric, super-amplified outcry, a sound so loud you can feel it in the fillings in your teeth; it’s the voice of your homeland, America screaming:

“A WOP-BOPPA-LOO-BOP A-LOP-BAM-BOOM!”

Good Golly, Miss Molly, it’s Little Richard!

Happy Birthday

Born Richard Penniman in Macon, Georgia, December 5, 1932, he’s still with us on December 5, 2007, his 75th birthday. He’s even doing Geico commercials, which I highly recommend, particularly the one with President Bush. A look at both versions on YouTube today will put a Happy-Birthday-Little-Richard smile on your face.

Did that barbaric yawp shatter the illusion of differentness for the dazzled youth? Not at all. After the shock came a patriotic shiver. You’d forgotten what a truly exotic country you’d left behind. But while this burst of happy American nonsense made the mix even richer for some of us, it was among the stress factors that sent our tour conductor, an award-winning political philosophy scholar at Oxford, literally around the bend. There were other factors: a traumatic involvement in the anti-apartheid underground; the landing on the shores of Lebanon by American marines; and the relentless babble of 36 American students, all but eight of them females, schoolteachers-to-be, who were more appalled than enchanted when Little Richard cut loose that first day. But above all, it was the neuron-shattering wildness of “Tutti Frutti” that inspired our bipolar guide’s scheme for turning the Golden Bear tour into a traveling rock-and-roll road show (“We shall sing for our supper!”). Found among his effects after the Oslo police led him away a week later (“I am not a tour conductor! I am a courier!”) were the lyrics to “The Logic Rock,” which began “Logic rock is the rock with a sock in it./Logic rock is the rock that gives/Get a little logic and put a little rock in it/Carry your water in logical sieves” and then: “Bring your Euclids down from your attic,/And start out rockin with an axiomatic./Never read Dummett? Never read Quine?/Then start back in with old Wittgenstein.”

Our tour leader was sure the Lebanon landing would lead to the Third World War, but what put him over the edge, the soundtrack for his paranoia, was the musical anarchy of Little Richard.

Tutti Frutti

Asked by a Rolling Stone interviewer back in the late 1960s how he came upon the joyous war cry I have loosely translated (more from memory than from the record itself), Little Richard said:

“Oh my God, my God, let me tell you the good news! I was working at the Greyhound Bus Station in Macon, Georgia, oh my Lord, back in 1955…. I was washing dishes…at the time. I couldn’t talk back to my boss man. He would bring all these pots back for me to wash, and one day I said, ‘I’ve got to do something to stop this man bringing back all these pots back to me to wash, and I said, ‘Awap bob a lup bop a wop bam boom, take ‘em out!’ and that’s what I meant at the time.”

“Good Golly Miss Molly” and “Long Tall Sally” were also written in that Greyhound Bus Station kitchen.

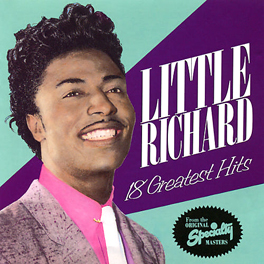

Listening again to these songs, which were inescapable at the time (you didn’t need to buy the records) and which have been remastered on the Rhino collection of Little Richard’s 18 Greatest Hits (available at the Princeton Public Library), the first thing that stands out is that you’re listening to straight-ahead, downhome rhythm and blues as opposed to the early rock n’ roll sounds of Bill Haley and the Comets or Elvis. Songs like “Long Tall Sally” and “Slippin’ and Sliddin’“ bring back summer nights driving around in a midwestern teenage wasteland listening to Little Walter, Little Milton, and Bo Diddley on WLAC, the clear-channel R&B station from Nashville, Tennessee. The raw excitement and the nutty lyrics gave us stir-crazy hayseeds at least the illusion of being part of an alien realm somewhere “rich and strange,” a high octane preview of the hitchhiker destiny foreshadowed that day in Delft.

The Happy Howl

Little Richard broke through in 1956, the same year Elvis did. For all his parent-scaring, hip-shaking bump-and-grinding, Elvis was not as wild as the sassy, swishy, pencil-thin-mustached black man with the beehive-hair-do who performed as if possessed — by either the holy spirit (he was expelled from Bible College on the way to recording two gospel albums) or by the gaudy spirit of his feverish imagination. Out of that inspired euphoria came the happy howl, which Don Waller’s Little Richardesque liner notes on the Rhino CD call the “Whoo.” When the Beatles wanted to drive their fans mad in the days they were evolving into mythical creatures, all John and Paul had to do was shake their heads and produce the happy howl. And as they were the first to admit, no other performer had as much to do with igniting their music and sending them soaring, neither Elvis nor Chuck Berry. And early on, both the Fab Four and the Rolling Stones opened for Little Richard, who claims a role in landing the then-unknown Beatles their first gig in Hamburg.

What lifts the prime Penniman recordings over the top is the playing of the group itself, most especially Little Richard’s relentless driving piano and the burning tenor sax solos of Lee Allen, which presage the ecstatic blowing of Clarence Clemons on Bruce Springsteen anthems like “Born to Run.” Along with the vocals, the sax drives every number, especially “Long Tall Sally,” “Slippin’ and Sliddin’,” “Rip It Up,” and “Good Golly Miss Molly.” And, of course, “Tutti Frutti.”

Waller’s liner notes for the Rhino set do a pretty good job of transposing to print the Little Richard style, and when you see the delirium of punctuation marks, the boldfaced capital letters, the verbal chaos, and all those primal grunts, growls, and howls laid out on the page, it conjures up the prose of Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, and Lester Bangs, all looking to find a style that would put American madness into words. Here’s an example:

“OHH! MY SOUL!…LITTLE RICHARD! LITTLE RICHARD! WOOOH! GONNA HAVE SOME FUN TONITE! LITTLE RICHARD!!!!!! WHHHHH-AAAAA00000HHHHH!!!!!…VERY TRULY THE GREATEST, MOST HIS ‘N’ HERSTERICAL ROCK ‘N’ ROLLER OF THEM ALL!!! WHOOO-OOOH!!! SHUT UP!!! SHUT UP!!!”

The Rhino booklet also features some photos, including one of Little Richard grinning like a rock n’ roll maharishi amid his devoted Beatles in the ashram of rock stardom. The best account of the man in action I’ve ever read is Greil Marcus’s description of him exploding out of his seat on the Dick Cavett show and running down into the audience and all around the theatre. Originally in the premiere issue of Creem, Marcus’s brilliant essay has been reprinted in his book Mystery Train, which the library has on order.

Although Little Richard’s glory days may be behind him, he’s been busy collecting honors. Besides being among the first group of performers inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he’s in the NAACP Hall of Fame, the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame, and just last year, the Apollo Theater Legends Hall of Fame. In 2004 he was number eight on the Rolling Stone list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time, and this year Mojo magazine put “Tutti Frutti” number one on their list of 100 Records That Changed the World.