|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 52

|

Happy Holidays!

|

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

|

Enlightenment came early for Don Van Vliet, better known as Captain Beefheart, who died on December 17 at 69. As he told Langdon Winner in a May 14, 1970 Rolling Stone cover story, it happened when his mother was walking him to school on the first day of kindergarten: “We came to an intersection,” he recalled, “and she walked right out into the way of a speeding car. I reached up with both hands and pulled her out of the way. She could have killed us both. It was then that I thought to myself, ‘And she’s taking me to school.’”

The terms of the kindergarten revelation surfaced some 25 years later when Captain Beefheart told a Melody Maker interviewer of “a new car that has headlights that help you go round corners — most cars can’t do that. It’s the same with people and music. Most people are driving cars with headlights frozen straight ahead of them. There’s no way they can see round the corners. Everyone is frozen in their attitudes.”

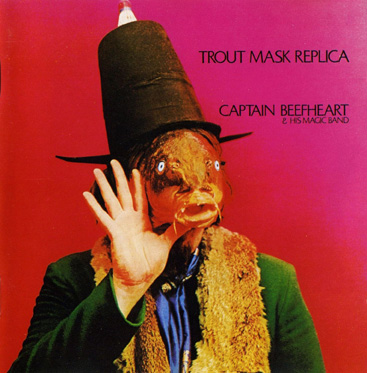

If anyone could see around corners, you have to believe it was the Captain. At the time of his death I’d been planning a year’s end column celebrating the 40th anniversary of the music that helped see a generation through the 1970 culture wars. My introduction to Beefheart had come the year before, however, with Trout Mask Replica, a double record set that I bought after reading Lester Bangs’s Rolling Stone review (“a brilliant, stunning enlargement and clarification of his art”). I took the album home, stretched out with my head between the speakers of our treasured KLH, and let the thing have its way with me. It was a memorable afternoon. Four sides of music. How I managed to get up and turn the record over and then get up twice for sides 3 and 4, I have no idea.

I must have been in an unusually receptive state that day because my experience was nothing like that of cartoonist and Simpsons creator Matt Groening, who needed six or seven listenings before he realized Trout Mask Replica was not just “a sloppy cacophony,” not “the worst thing” he’d ever heard, but “the greatest.” I had some anxious moments during the saxophone free-for-all in “Hair Pie: Bake One,” but the riffing guitars, “fast and bulbous” counterpoint, and staggered rhythms of the Magic Band powering concoctions like “Ella Guru” and “Moonlight in Vermont” made for an experience roughly comparable to being backed into a corner by the Ancient Mariner. For a piece of orchestrated chaos, the record was brilliantly coherent, the pieces meshing in divine discord as the Captain’s ship of fools rode waves of its own making, blown over a stormy sea by the out-there bellowings of its relentless, unsparing skipper. By the end I felt that I’d followed Beefheart across a poeticized semblance of that early intersection, emerging shaken but safe on the other side of a monumental, unprecedented work. I never listened to the whole album straight through again. Too much heavy traffic. One time was enough.

A Scary Show

When I saw Beefheart and the Magic Band at Bristol’s Colston Hall on the first stop of their 1972 British tour, my expectations were unrealistic. I was looking for a live version of that head-between-the-speakers experience. In the big hall, with its unstable sound system and a stoned-to-the-bone audience devoutly craving to be amazed, it was a demolition derby: two-way traffic on a one-way street. That the show opened with a ballerina and a belly dancer suggested an elaborate practical joke out of Terry Southern’s Magic Christian, with the inscrutable Beefhart wrapped in a black cape like Guy Grand teasing devoted fans desperate to be in synch with every crazed nuance. Comparing this show with a later one in London, a Melody Maker review said London was musically better but that the “warmth and atmosphere” projected by the “magic” Bristol audience made that the preferable performance.

Once I’d adjusted my expectations, I got into the show enough to begin seeing the band as a sort of magical musical Penny Arcade pinball machine with Rockette Morton (Mark Boston), Mascara Snake (Roy Estrada), Zoot Horn Rollo (Bill Harkleroad), and Winged Eel Fingerline (Elliot Ingber) popping up and bouncing about powered by an invisible assemblage of gears and levers and pulleys, the most dynamic of these figures being Rockette Morton, a film noir hipster sharpie in a pork-pie hat and a white rainbow-streaming suit, a cigarette in his mouth as he steam-engined back and forth across the stage, pounding his guitar like a barber stropping a razor, thrashing, churning, forwards, backwards in automated tangents on a system of tracks I imagined being controlled by the drummer engineer. While the two lead and two bass guitars stoked the electric fire, Captain Beefhart was lumbering bearishly about with a soprano sax from which he was producing sounds like birds in flight beaten this way and that by the Magic Band only to fly free again and again, careening from wall to wall. I finally had to close my eyes to hear all those parabolas, so much sheer sonic traffic that for a time I had what I’d come for: caught in the old intersection crossfire just as it had been that day with my head between the speakers.

Year of Wonders

The KLH was new in 1970, the first good sound system we’d ever had, bought at long-gone and still lamented Hi Fi Haven in New Brunswick. If Trout Mask was music to throw yourself in front of, George Harrison and Phil Spector’s great wall-of-sound coup, All Things Must Pass, was music to jump for joy to, and jump we did whenever “What Is Life?” was playing, the volume way up. Though the KLH speakers were not the big top-of-the-line ones, they put out enough sound to set the living room rocking while we imagined our poor landlady cowering in the room below as plaster rained and glasses rattled.

Phil Spector’s magnificent job for George Harrison was in contrast to the uninspired production he gave Let It Be, which had come out that spring. Possibly the least charismatic Beatles album ever with its dull cover and posthumous downside, it still provided music you could live in, like “Two of Us,” “Across the Universe,” and “Dig a Pony.” In May, McCartney’s first solo album gave us one of his most memorable compositions, “Maybe I’m Amazed,” but the song to reckon with that year was Lennon’s “Instant Karma,” which he rushed out in February (“wrote it for breakfast, recorded it for lunch, and we’re putting it out for dinner” he told the press). Spector’s production on that cry from the heart made up a little for the lackluster job on Let It Be.

What a year. You had the Grand Guignol of The Man Who Sold the World from David Bowie, Sunflower from the Beach Boys with Brian Wilson’s sublime “This Whole World” and Procol Harum’s Home, which contains “Still There’ll Be More,” the most euphoric put-down song ever written (“I’ll blacken your Christmas and p--- on your door”). Speaking of inspired put-downs, the master Randy Newman released his 12 Songs that year, and while no one song stood out on The Band’s Stage Fright, the LP was one we played many times. Van Morrison’s Moondance was disappointing only if you’d been hoping for another Astral Weeks. The record that came closest to equaling that album’s complex, haunting atmosphere was John Cale’s Vintage Violence, where masterful numbers like “Gideon’s Bible” and “Ghost Story” somehow coexist with banalities like “Cleo.”

Two addictively listenable albums were Rod Stewart’s Gasoline Alley and Fleetwood Mac’s Kiln House, while two of the best songs of the year (“Sweet Jane” and “Rock and Roll Music”) came from The Velvet Underground’s Loaded.

From the Kinks there was Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, which at the time was overshadowed by its predecessor, Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire), but Powerman was a grower that gave the world great songs like “Get Back In Line” “Strangers” and “This Time Tomorrow.”

Then there was Layla and Other Love Songs by Derek and the Dominoes, wherein two inspired musicians, Eric Clapton and Duane Allman, bonded on the spot. When a mere machine like the KLH provides pleasure of such quality, you begin to have fond thoughts, like taking it out to dinner or stringing the speakers with Christmas lights, and it always seemed to outdo itself when the title track of Layla was playing. Besides being one of the most passionately uninhibited love songs ever written, “Layla” has a second act like nothing else in rock, that stirring moment when the guitars lay back, making way for the piano, and then come round again even more gloriously than before. When that happens, you know what Beefheart meant by seeing around corners.