|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 53

|

|

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 53

|

|

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

|

|

Metaphors are our way of losing ourselves in semblances or treading water in a sea of seeming.Roberto Bolaño

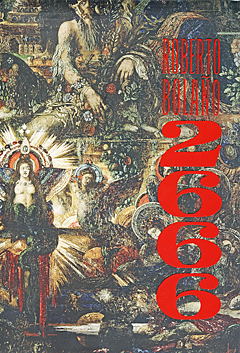

So here we go across the frontier of years and what better company for the passage to 2009 than Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous 893-page wonder 2666 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux $30), which Kirkus Reviews called “the finest novel of the present century,” adding that “we may be saying the same thing 92 years from now.” The New York Times settled for listing it as one of the Ten Best Books of 2008. Other blasts from the fanfare of acclaim: 2666 is “epochal,” “truly mesmerizing and breathtaking,” “a heroic achievement, a modern epic, a masterpiece,” “a literary blockbuster,” “inescapable, unignorable, and lasting,” “an exceptionally exciting literary labyrinth” that “exerts a terrible power over the reader long after it’s done.” The Los Angeles Times has the author writing “in a race against death” (and so he was) “to make some final reckoning, to take life’s measure, to wrestle to the limits of the void” while in the New York Times Jonathan Lethem speaks of “a landmark in what’s possible for the novel as a form in our increasingly, and terrifyingly, post-national world.” Even the less admiring responses were intriguing. Time called it “a dangerous book … you can get lost in it” and Newsweek suggested that “if you’re a reader who’d rather see a novelist aim for the moon, even if he falls on his face, then this is the book for you.”

Surprisingly enough, the New Yorker, which in 2007 ran a lengthy, intelligent piece about Bolaño and his previous novel, The Savage Detectives, bypassed the challenge with an “In Brief” item that after calling 2666 “a compendium, in individual scenes, of the qualities that made him a great writer,” huffily wishes that by the end “the novel cohered, rather than merely concluding.” What a puny, sniveling, wretched beggar of a word is cohered. It’s as if the nameless writer of that squib threw a styrofoam pellet, not even that, but the semblance of a styrofoam pellet, at a gale-force wind. Is it any wonder that a character in 2666 finds “all criticism … ultimately a nightmare”?

Getting Lost

First things first: I loved reading this novel, though to say you “loved” reading the fourth and longest section, “The Part About the Crimes,” would be a stretch since it’s mined with the brutalized bodies of girls and women. You might as well say you love hell. The best book I read in 2008, next to this one, was Bolaño’s previous novel, The Savage Detectives. What a blessing, that books as rich as these can even see the light at a time when the publishing business seems to be sinking along with the rest of the economy. I would gladly read the whole novel over again, right now, if only because then I might have a better shot at doing justice to it. I could also have gladly re-read Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day and the wild, bumpy ride of a novel I wrote about in early 2008, Alexander Theroux’s Laura Warholic. But neither of those immense works presented quite as massive or seductive a challenge. Consider the following exchange from the second section of 2666, “The Part About Amalfitano,” where the title character, a Chilean literature professor, is living out his exile in the haunted film noir city of Santa Teresa (“a capricious and childish beast that would have swallowed Heidegger in a single gulp if Heidegger had had the bad luck to be born on the Mexican-U.S. border”). The exchange comes after one of numerous instances of Bolaño using Amalfitano’s exotic, brilliantly articulated paranoia as a vehicle for his own ideas about fiction and criticism and “shadowless intellectuals” who strive to “maintain the discipline of meter where there’s only a deafening and hopeless silence.” After hearing Amalfitano hold forth brilliantly on “the loss of one’s shadow” in the course of a breathtaking monologue, the female member of the trio of critics who have come to him for information about a German novelist named Benno von Archimboldi tells him, “I don’t understand a word you’ve said,” to which Amalfitano replies, “Really I’ve just been talking nonsense.”

And if you’ve read this far (page 123), you may already find yourself saying of Bolaño, as Ronald Reagan once said of Walter Mondale, “There he goes again!”

You may also be reminded that tomorrow, January 1, 2009, will be J.D. Salinger’s 90th birthday, because it was Salinger who once dedicated a book to “the amateur reader,” the one “who reads and runs.” (Compared to the mysterious Archimboldi, Salinger is a publicity hound.) It’s not that Bolaño disdains the “serious” reader, i.e. critics and reviewers. He loves ’em to pieces; he’s given them a whole world to explore. But like Joyce and Sterne and Pynchon, he enjoys creating labyrinthine traps for them to scamper inventively or foolishly around in. The Time reviewer had it right: this is a dangerous book and you can get lost in it.

On the Title

When he began the book in the late 1990s, Bolaño knew he might not live to finish the job, but by the time he died of liver cancer in 2003, he’d essentially completed the writing, and a year later, 2666 was published in Spain by Editorial Anagrama. Although he originally conceived of the novel as something comparable to the “literary blockbuster” reviewers have called it, at the time of his death he hoped to issue it as a series of five novels in order to generate more income for his children’s future. Farrar Straus has reached a quasi compromise by publishing Natasha Wimmer’s translation both as a single hardcover volume and in a three-volume paperback set.

According to an afterword by Bolaño’s literary executor Ignacio Echevarría, the “final version” of the novel is “clear and clean” and “very nearly” what the author “intended it to be,” though he undoubtedly would have worked longer on it (“but only a few months longer”).

As for the significance of the title, the most likely clue that Echevarría can offer comes from Bolaño’s short novel, Amulet (1999), where a street in Mexico City is conceived to be “more like a cemetery than an avenue, not a cemetery in 1974 or in 1968, or 1975, but a cemetery in the year 2666” — “a forgotten cemetery under the eyelid of a corpse or an unborn child” (an image Salvador Dali could do wonders with). When Natasha Wimmer was asked what she thought the title meant, she told a New York Magazine interviewer that for her “it signifies remote, incomprehensible malevolence.” In a novel with evil on the grand scale at its center and three of its five parts directly concerned with the rape, torture, and murder of hundreds of women (not to mention Part Five’s picture of barbarism on the Russian front in World War II), it seems naive not to at least acknowledge (as Wimmer does) the presence of 666, the number of the beast from the Book of Revelations. Pronounce the title numeral by numeral in English and you don’t have to be a compulsive punster to hear “sex” for “six,” which makes a kind of sloppy sense in a book bursting with sexual energy.

Sexing Up the Intelligence

Bolaño is great because he gives so much. So much imagination, so much invention, so much music, so much sheer literary pleasure. He’s earthy and baroque, slinging metaphors and “semblances” (or apariencia, one of the most stressed and loaded terms in the book) like a drunken cowboy on a shooting spree; he rocks and he rolls; he’s a one-man band. With his vagabond sensibility, he’s at home anywhere in the world. He can be as twistedly sinister as David Lynch at his scariest, and then turn around and spin prose cadenzas that make you think of Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins.

The sexual energy I mentioned is another of Bolaño’s gifts. Women and girls in 2666 are more often than not attractive, fascinating, desirable, intelligent and creative beings, which makes an unsettling and yet somehow exhilarating contrast to the multitude of woman and girls whose bodies weigh so heavily on the narrative in “The Part About the Crimes.” The first female character in the book is a Brit named Norton, the eminently desirable critic who admitted that she didn’t understand a word of what Amalfitano said. Bolaño’s insistence on referring to her by her last name in the book’s first section, “The Part About the Critics,” is a subtle form of titillation. You know that sooner or later that these “last names” are going to get physical, which happens when Norton has sex, alternately, with both the Frenchman Pelletier and the Spaniard Espinoza, only to settle down with the Italian Morini. And it’s no coincidence that after hearing that incomprehensible dissertation on “shadowless intellectuals,” she decides to take both Pelletier and Espinoza to bed with her for the first and only time.

A Torrential Work

While Bolaño may never have actually called 2666 his Moby-Dick, he must have conceived of the documentation of evil in Santa Teresa as a gruesome version of Melville’s scholarly documenting of whaling and whales in Moby-Dick. He’s almost certainly reflecting on his own project when he has Amalfitano thinking it “sad” that an eager young reader would choose Bartleby over Moby-Dick among Melville’s creations for fear of taking on “the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze paths into the unknown” and “struggle against that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.”

On that note, one of numerous instances where Bolaño offers critics and reviewers juicy quotes with which to describe 2666, I have to close up shop without so much as scratching the surface of the third section, “The Part About Fate,” in which an African American reporter who uses the pen name Oscar Fate finds himself in Santa Teresa falling in love with Amalfitano’s daughter, Rosa, while steering her through a miasma of sheer menace that makes David Lynch’s Twin Peaks seem like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. It was this section, which begins in Detroit, that Natasha Wimmer found the “trickiest” to translate: “Try channeling an African-American narrator as imagined by a transplanted Chilean who never set foot in the United States.”

And try getting at 2666 in under 2000 words. Maybe I can manage a sequel.

Last Words

According to the afterword, Roberto Bolaño left this note for the end of 2666: “And that’s it, friends. I’ve done it all. I’ve lived it all. If I had the strength, I’d cry. I bid you all goodbye.”

Three copies of 2666 are at the Princeton Public Library. Don’t let the length discourage you. This is a wonderfully readable book, a joy, in fact. And don’t let “The Part About the Crimes” scare you away. The next and concluding section, “The Part About Archimboldi,” is teeming with riches that will send you right back to the beginning.