|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 5

|

|

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

|

|

|

A note can be as small as a pin or as big as the world. It depends on your imagination.— Thelonious Monk

Usually I listen to Schubert on his birthday, which was this past Saturday, January 31. I’ve been doing it ever since my then-three-year-old son suggested getting a special cake for the occasion. But this year, every day from the day Barack Obama became president, I’ve been playing Thelonious Monk. While Obama’s election puts a glow on this particular Black History Month, and while I was due for a record review, and while jazz and black history are virtually synonymous, what my recent Monk binge really comes down to may be a subliminal reaction to Rev. Joseph Lowery’s extraordinary Inaugural benediction. Something about the way he came looming up over the podium, the big grizzled man all but singing James Weldon Johnson’s words in his richly raspy voice (“God of our weary years, God of our silent tears”) could well be what made me forget about Schubert.

But not for long. As I was driving down Harrison Street Saturday with “Crepuscule with Nellie” on the stereo, I was reminded of one of those moments in the late piano sonatas when you can almost hear Schubert breathing, feel him thinking. That’s when I realized whose birthday it was. As soon as I got home, I went straight to Alfred Brendel’s recording of the Sonata in G, put the needle down on the minuet, a mere four minutes of music that, as I knew it would, put me back where I’d been with “Crepuscule with Nellie,” a deceptively simple, deeply evocative creation with a heart “as big as the world.”

Nellie, by the way, was Monk’s wife, and it was thanks in great part to her guidance and counsel that he remained in action, on the planet, as long as he did. Although he died at 65 in 1982 (20 years before his wife), he’d begun his slow fade from reality in the early 1970s. On his final tour in 1971, according to bassist Al McKibbon, he only said “about two words. I mean literally maybe two words.” You can hear Monk say half a dozen words on a YouTube clip from French television in 1969. His voice is soft, gentle, vulnerable, and it’s a boy’s smile you see when he looks up at his French host after putting the last touch on “Crepuscule with Nellie.” When he’s asked “what is the name of this tune please,” he thinks a bit, and then pronounces the title as if he’d just that minute thought of it.

The Blindfold Test

It’s still hard to grasp the fact that back in the 1940s and 1950s so many musically oriented people, including other players, couldn’t “hear” Monk. Musicians listening to his records during the Blindfold Tests Leonard Feather conducted for Down Beat magazine over the years as often as not patronized his playing. “He writes some beautiful tunes,” one said, “but when it comes to being a piano player, I’ll see you later.” The truth is that with few exceptions other pianists appreciated what he was up to. After admitting that classical performers had “nothing to worry about” from Monk, Bill Evans declared him “pianistically beautiful,” notably in the way “he approaches the piano somehow from an angle, and it’s the right angle.” Pianist Hampton Hawes had one of the most enlightened reactions. Suspecting that the record being played was by Monk, but not sure, he said, “That piano player sounded honest as a little child.” He went on to observe that he’d rather “hear wrong notes being played by a person with good feeling than another person playing perfect.”

It’s not that Monk plays wrong notes. He just makes wrong notes right. Gary Giddins’s definitive piece in Visions of Jazz uses an epigraph that picks up on what Bill Evans was talking about. The quote is from Nellie Monk, who tells of how her husband cured the phobia she had about pictures or anything hanging on a wall “just a little bit crooked.” Nailing a clock to the wall at a very slight angle, Monk insisted on leaving it that way. She was furious. They argued about it for hours, but she finally got used to it, admitting, “Now anything can hang at any angle, and it doesn’t bother me at all.” From what I’ve read about their nearly 50-year relationship (she was 11 when they first met), she won more arguments than he did. A New York Times piece written after her death said that he had great trust in her opinions, that she used to tape record his playing at home so she could advise him, and that while he was at the piano, she would sometimes sing along “in unison.”

Speaking of the Blindfold Test, the only one Monk ever agreed to take part in himself was in 1966 and it was on the condition that Nellie would be there. Sure enough, when he was asked how he’d rate a certain record, he said, “Ask her.” Another time, after an amused if exasperated Leonard Feather asked him if he thought Bud Powell was “in his best form” on a record where he clearly wasn’t, Monk began stalling until Nellie set things straight, telling him, “You don’t think so,” which got him to admit, “Of course not.”

One of the most Monkish things Monk said in that chaperoned Blindfold Test surfaced when Feather once again tried to pin him down, in this instance about Art Pepper’s version of the Monk tune, “Rhythm-a-ning.” After Monk mentioned hearing “a note that’s not supposed to be there,” Feather asked “Did I hear you say the tempo was wrong?” Monk’s reply was “No, all tempos is right,” a notion reflected in what singer songwriter Stew of Passing Strange fame points out in his love song for Monk, “In Time All Time” (“It’s like my birthday every day/Cause Mr. Monk is such a ray of wisdom and light/He dried all the fears from my eyes/And in time all time will be time”).

Monk’s time, in the worldly sense of the word, was slow in coming. In his piece, Giddins contrasts the long and winding road of Monk’s reputation with the immediate impact of players like Louis Armstrong whose voice was “so startling … that the whole music seems to stop.” As for Monk, “he labored in solitude for much of his most creative period. His records were ignored, his compositions pilfered, his instrumental technique patronized, his personal style ridiculed. Yet no voice in American music was more autonomous and secure than Monk’s.” As for his influence on other major figures, suffice it to say that much of the style, wit, and rowdy force of Sonny Rollins can be traced back to the man he calls his “guru.”

Anniversaries

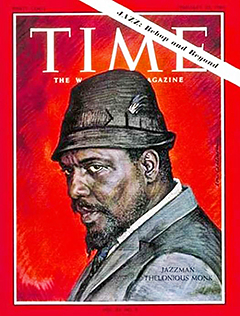

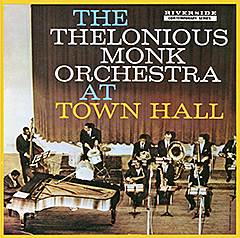

The month of February contains some significant anniversaries for Monk, whose Town Hall concert 50 years ago, February 28, 1959, was a turning point in the history of his acceptance as a major figure in American music; five years later, his face was on the cover of the February 28, 1963, issue of Time, which made him a major figure, period. The Town Hall event, for which he headed a ten piece ensemble, not only represented a “coming out” for the solitary and misunderstood musician Giddins described, it produced a record that does him full justice. He closed the concert proper with, no surprise, a spirited rendition of “Crepuscule with Nellie.”

Through it all Thelonious Monk sustained his personal equilibrium. As his producer at Riverside, Orrin Keepnews, puts it on YouTube: “He was as indifferent to the trappings of success as he was to the trappings of failure.”

A thorough exploration of Monk on YouTube brings all kinds of special pleasures if you want to see and hear what he’s all about. You can watch him pound and pummel the piano with a verve and vehemence that would impress both Jerry Lee Lewis and Chico Marx. And you can see him do his “dance,” which sometimes consists of moving slowly around in circles and other times of pacing in a self-abstracted back and forth, his own version, perhaps, of a dance to the music of time. Chuck Berry duckwalks. Monk monkwalks. At “Internet Sightings: Memories of Monk,” you can read a handwritten series of reflections in the man’s own hand, including the one at the top of this article.