|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 8

|

|

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

|

|

Scene: A filled-to-capacity classroom at a large midwestern university. The teacher enters wearing his raincoat like a cloak, sidles over to a row of windows and lowers the Venetian blinds, further dimming an already dark winter day one immemorial year on the cusp of the sixties. Disposing of his raincoat cloak with a sinister flourish, he advances to the blackboard, picks up a piece of chalk, tilts his craggy face at a sly angle, grinning over his hunched shoulder at the overflow student audience as he intones, in a husky, theatrically intense Virginia accent that already has the groupies in the front row swooning, “Today we are going to talk about — Edgar … Allan … Poe.”

What his Virginia accent does to “Poe” sends another shiver through the maidens up front. He’s not merely speaking the name, he’s summoning the owner, as if Poe, like the ghost in Hamlet, were waiting in the wings. Chalk in hand, he bends forward, arching his shoulder slightly, and draws with loud swift strokes three immense letters.

P O E,

to which he adds a tiny “t.”

“Not quite a poet,” he says.

Once he begins speaking, it takes little more than a telltale heartbeat for him to move from the notion of “poet “ to the theme of “pose.” An hour later a roomful of stunned students emerges from the misty mid-region of Weir. As the mundane reality of the campus sinks in, they begin talking, nudging one another, smiling, some of them already delightedly recreating the theatre of their hero’s entrance. They revere him, they revere Poe through him, and chances are, he’s the best teacher any of them will ever have. So went one of the classic literary seances conducted at Indiana University by James M. Cox.

Poe and Kilroy

You can be sure Jim Cox apprised his students of the fact that the “divine Edgar” (as James Mason’s Humbert Humbert has it in Stanley Kubrick’s film Lolita) and the great emancipator were born less than a month apart in the same year, Poe on January 19, Lincoln on February 12.

Two hundred years later, while Lincoln watches over the world from the Lincoln Memorial, it’s Poe who haunts the land, peering out from the shadows, a scene-stealer of awesome dimensions, and a major figure in Hollywood and film studios around the world where more than 200 adaptations of his work have been released (Tell Tale recently completed, Horror Vault 3 in progress), according to the international movie database. Rock bands have improvised on and celebrated his tales and poems, and some have borrowed his name. His raven has been attacked by Homer Simpson and adopted by a pro football team from the city he died in — a death almost as central (or sub-central) to the national memory as the death of Lincoln. (Too bad the Baltimore Ravens didn’t make the Super Bowl; it would have been a perfect way to mark Poe’s 200th.) You can laugh at or with him (he can be very funny) but in whatever guise — mad genius, knave, storyteller, cryptologist, philosopher, medium — he’s a prodigious figure. In terms of the ruling American standard — big bucks — he tops the charts. Were you to happen on a first edition of his early poems or of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, you could move to the Riviera and set up a Swiss bank account.

No other writer, not even Whitman, is as familiar a figure in the American narrative. The actual amount of Poe I’ve read in print is minuscule compared to the amount I’ve breathed in simply by living in the culture. While Poe and Lincoln are two of the most instantly recognizable faces of America (both featured on new stamps), Poe is like Kilroy; he’s everywhere, including the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, smack dab in the center of the back row between Bob Dylan and Dante. And it’s Poe’s rough and tumble ride through posterity that John Lennon’s citing in “I am the Walrus” when he sings “Man you should have seen them kicking Edgar Allan Poe.” Listen to the snippets from a BBC broadcast of King Lear at the close of “I am the Walrus” and Poe comes to mind again; he’s America’s wise Fool, or else a poseur assuming that guise, like Lear’s Edgar posing as Tom o’ Bedlam. Or he could be Richard the Third in the eternal winter of his discontent, a role played by John Wilkes Booth, who looked enough like Poe to suggest fantastical travesties such as one where the John-Wilkes-Booth lookalike Poe lives long enough to speak for the South in the Civil War and stand in for Booth on April 14, 1865, at Fords Theatre. Gaze deep enough into the weird nooks and crannies of American history and you find that Booth was known for giving dramatic recitations of “The Raven,” a poem that also happened to be close to Abe Lincoln’s heart, so close that in his melancholy fits, he might have dubbed himself Nevermore.

Poe and Lincoln

Yes, it’s true, you can look it up: Poe was Lincoln’s favorite American writer. The recently published multi-editor tome, Looking for Lincoln, has Lincoln adding to his ghostwritten autobiography the fact “that he possessed a lifelong love for the stories of Edgar Allan Poe.” According to Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Lincoln knew and liked not only “The Raven,” but also Poe’s short stories, notably “The Gold Bug” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” According to Joshua Wolf Shenk’s Lincoln’s Melancholy, when Abe was a lawyer riding from town to town on the Eighth Judicial Circuit in Illinois in the early 1840s, his law partner remembers him reading “The Raven” over and over by candlelight.

It was Lincoln’s own poetry that brought Poe’s into his life. Benjamin Thomas’s 1953 biography, Abraham Lincoln, has Lincoln sending some of his poems to a lawyer named Johnston, among them one reprinted in Lincoln’s Letters & Addresses that begins as a familiar paean to “childhood’s home” and ends in Poe country where “every sound appears a knell,/And every spot a grave.” In the closing stanza, you can even hear an echo of Coleridge, whose fate-inflicting albatross in the “Ancient Mariner” anticipates Poe’s raven: “I range the field with pensive tread,/And pace the hollow rooms,/And feel (companion of the dead)/I’m living in the tombs.”

Johnston’s response was to send Lincoln a parody of “The Raven,” in which an experience with a polecat replaces Poe’s midnight visitor. It was this exchange that apparently moved Lincoln to seek out Poe’s poem, published the previous year, which suggests that Lincoln had a constitutional kinship with Poe before he actually read “The Raven.”

Value

In the rare book branch of the literary stock market, there is a clear relationship between an author’s critical reputation and the price book dealers feel they can get for first or rare editions of a work. Poe’s extraordinary market value derives from his association with hot genres and the attendant film tie-ins (mystery, detective, noir, horror, science fiction), no less than from the scarcity of the early printings of his poems and tales. The same could be said of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, first editions of which would not be fetching quite such stratospheric prices but for Universal Pictures and Boris Karloff and the culture’s fascination with the concept of the monster. It’s safe to say, however, that even without the movies, the same books by Poe would still be at the top of the list, along with obvious literary landmarks such as Moby-Dick and Leaves of Grass. Poe’s market value is solid because his persona — or, to put it crudely, his trademark — transcends the fine points of literary value for which he’s been judged lacking by the likes of James Russell Lowell (“Here comes Poe with his raven, like Barnaby Rudge — /Three fifths of him genius, and two fifths sheer fudge”); Henry James (“To take him with more than a certain degree of seriousness is to lack seriousness one’s self”); W.B. Yeats (“an appeal to the nerves by tawdry physical affrightements”), Aldous Huxley (“one of Nature’s Gentlemen, unhappily cursed with incorrigible bad taste”), and any number of critics who treat him as a vulgar interloper in the hallowed domain of literature. For so immense, even mythic, a figure, these slights only help perpetuate the legend.

In any case, Poe has some formidable defenders, among them William Carlos Williams, Edmund Wilson, Allen Tate, and George Bernard Shaw. Writing a few days short of Poe’s 100th birthday, Shaw includes him among the great writers “who begin just where the world, the flesh, and the devil leave off” and declares, “If the Judgment Day were fixed for the centenary of Poe’s birth, there are among the dead only two men born since the Declaration of Independence whose plea for mercy could avert a prompt sentence of damnation on the entire nation … Poe and Whitman.”

Now, in Edgar Allan Poe’s bicentenary year, Baltimore and Philadelphia are duking it out for bragging rights, along with New York and Richmond, Virginia. It seems that everyone wants to lay claim to a forever ambiguous figure who is as indispensable to the American imagination as Lincoln is to the American spirit.

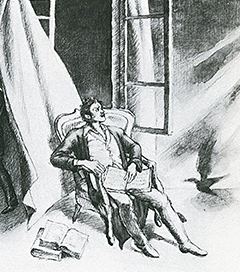

Note: The most appealing recently published collection of Poe’s tales is The Mystery Writers of America’s In the Shadow of the Master (Morrow $25.99), edited by Michael Connelly, which features companion articles by various writers in the genre, including Jeffery Deaver, Sue Grafton, and Stephen King. I found the quotes from James, Yeats, and the others in The Recognition of Edgar Allan Poe (University of Michigan Press). The image of Poe pondering “The Raven” is a detail from a carbon pencil and wash done in 1980 by Edward Laning (1906-1981), one of several studies on themes from American literature he was working on for the New York Public Library Periodicals Room when he died.