|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 1

|

|

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 1

|

|

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

|

|

|

“I am moved to put Chaplin with the poets (of today)…. Chaplin may be a sentimentalist, after all, but he carries the theme with such power and universal portent that sentimentality is made to transcend itself into a new kind of tragedy, eccentric, homely and yet brilliant.”

—from The Letters of Hart Crane

In October 1923 in New York, the American poet Hart Crane spent a night carousing and conversing until dawn with Charlie Chaplin, who admired Crane’s poem, “Chaplinesque,” and was said to be interested in his work. At the time of their meeting, Crane was relatively unknown and little read while Chaplin was a world-renowned celebrity. The comedian would die a wealthy man at the age of 88 on Christmas Day 1977 (his villa in Switzerland is being turned into a museum). The poet was only 33 in April 1932 when he apparently took his own life by jumping off the stern of a ship bound for New York from Mexico.

After his night with Chaplin, Crane wrote to his mother: “I am very happy in the intense clarity of spirit that a man like Chaplin gives one.” According to Waldo Frank, who brought Chaplin and Crane together, the poet committed suicide because his “excesses” had “crowded out the crystal intervening times when he could write.” It seems likely that his “clarity of spirit” coincided with those “crystal” times when he was writing. Maybe he’d have made it back to New York if they’d been showing City Lights on board the Orizaba.

In “Chaplinesque” Crane tries to get at the source of the quality that gives Chaplin’s films their compassionate universality. He uses a kitten as, in his words, the “symbol” of the actor’s “social sympathies.” The second stanza begins: “For we can still love the world, who find/A famished kitten on the step, and know/Recesses for it from the fury of the street.” The poem ends with the poet hearing “through all sound of gaiety and quest…a kitten in the wilderness.”

“Chaplinesque” is a hard poem to quote fairly, and, like much of Crane’s work, it doesn’t offer an easy reading. Chaplin’s “power and universal portent,” however, are among the virtues that made the actor/director the only poet of cinema with the ability to touch audiences worldwide at every level of society. Presumably you could convene a group composed of total opposites or even mortal enemies and seat them in the same theatre (as long as the house lights were down, anyway), billionaires and bums, arch conservatives and far-left liberals, zealots and atheists, and if anyone could have them laughing and even crying together, it’s Chaplin.

The Heart of New Year’s Eve

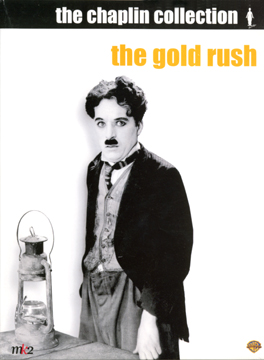

New Year’s Eve being possibly the most universally observed holiday, it makes sense that the most universal of artists would be the one to find a way to the heart of the occasion. All Chaplin needed was a Gold Rush saloon, some dance hall girls, a rose and a photograph, a prospector’s cabin, a couple of dinner rolls, and his alter ego, the resourceful and ultimately indomitable tramp whose genius for pathos and comedic choreography makes him the master of every scene, especially the ones in which he plays the hapless fool. The medium for the audience’s engagement with Chaplin’s art is the headstrong dance hall girl, Georgia (Georgia Hale), who begins by patronizing the tramp as a laughable loser and then watches him progress from an amusing curiosity to an emotional touchstone to a gold rush millionaire.

Chaplin uses an age-old Hollywood formula — the wooing of a beautiful woman against great odds — to develop two of the most sublimely felt sequences in all cinema, the ending of City Lights and the New Year’s scene in The Gold Rush. To Georgia and her girlfriends from the dance hall the “little fellow” (the preferred term in Chaplin’s narration of the 1942 reissue) is a figure of ridicule. The best they could say of him is that he’s cute. How can Georgia take seriously someone dressed like a travesty of a fallen dandy with a penchant for creating chaos and catastrophe?

When he invites the girls to New Year’s dinner in the shack he’s “housesitting” for a prospector, they don’t take him seriously. But the audience does, watching him shovel snow (the same pile, from one storefront to another) to earn enough to buy dinner provisions, along with the little presents he wraps for each girl, and the roast he cooks, and the festive table he sets, complete with candles and napkin rings. His guests never show up, of course, and while sitting at the table waiting for them, he dreams what would have happened if all had gone as he’d hoped. His dream self is confident and charming, the girls love him (a reflection of the reality enjoyed by Chaplin, the adored star), and Georgia is his. Instead of making a speech to express his joy in the event, he pantomimes a dance using two dinner rolls on the prongs of two forks, each roll becoming a miniature version of each of his own oversized shoes as he impassively puts them through their paces, moving his head left and right to follow the kick of each leg. With the soft light of the candles glowing on his face, the dream dance takes on an almost hypnotic fascination. You become a child again watching it. The audience response at the time was extraordinary; in some theatres people kept clapping until the film was stopped and the sequence shown again. When the tramp wakes up after midnight and comprehends the truth, he goes to the doorway and stands sadly staring toward the dance hall, where the music and tumult of the celebration can be heard. The subsequent shot of the “little fellow” standing outside looking through the window at the gay scene would seem to be as far as the pathos of the scene could be taken, Chaplin having isolated in his own person the human common denominator of loneliness and disappointment. But there’s more. When Georgia and her boyfriend and the other girls drop by after midnight to have some fun at the tramp’s expense, Chaplin adds the final touch. Georgia is the first to enter the shack, which is empty. Everything the scene is saying is in the expression on her face when she sees the festive table he’d prepared for them.

Georgia Hale is the perfect actress for that moment. She seems truly touched and saddened, and the audience shares the feeling with her. But she could not meet the more profound challenge of the climactic moment in City Lights.

“I Can See Now”

Like the wooing of the dance hall beauty, the tramp’s courting of the lovely blind girl in City Lights begins with a fallen flower. And in the same way that he worked to raise money for the failed New Year’s dinner, the tramp does everything he can think of (including prizefighting) to raise money for the operation that will restore her sight. She knows only his voice and the touch of his hand, and when, thanks to his efforts, she can see again, she’s hoping the handsome prince she’s imagined will eventually show up in the flower shop. Looking at the street from the front window one day she sees a funny little tramp shaking his fist at some newsboys who have been tormenting him. Her patronizing smile is much like the one that crosses Georgia’s face the first time the tramp walks into the saloon. Seeing him picking a fallen flower out of the gutter, the flower girl takes a single rose and calls him over, intending to give him a coin along with the flower. When their hands meet, she recognizes him through the touch. Shaken, she feels along his arm, as she felt it when she was blind. He smiles miserably and asks, “You can see now?” She nods; she’s still reeling. “Yes, I can see now,” she says, pressing his hand. The question and answer seem all the more momentous because they are spoken in silence. The audience sees the words on title cards. The silence deepens the moment, giving weight to each gesture, each dawning expression. This wretched being is her handsome prince, her rich benefactor. The depth of the recognition is a world beyond Georgia’s compassionate moment in the empty shack. This is something that simply confounds comprehension.

Moviegoers for all time should thank the fates that Chaplin didn’t fire Virginia Cherrill, the actress who beautifully plays the flower girl and measures up to every stunning, subtle emotional nuance of that scene. All you have to do to appreciate Cherrill is to see the test Georgia Hale made of the same scene, which is among the special features included in the Chaplin Collection DVD of City Lights. Chaplin reportedly made the test in desperation because his lead actress was coming to work hung over from partying the night before; she was living on alimony and was so hard to work with that Chaplin almost gave up on her. The test shows Georgia Hale trying and failing again and again to get the crucial gestures and expressions right; she’s too bright and earnest, still too close to the headstrong dance hall girl in The Gold Rush. She can’t feel the scene. Needless to say it was a lot to ask of someone who hadn’t had a chance to grow into the part. So, luckily for generations of audiences, Chaplin went back to Virginia Cherrill. Without her tender expression of shock, disbelief, and aching gratitude, Chaplin’s tortured smile — the subject of one of the most memorable close-ups in the history of cinema — would not radiate the “clarity of spirit” nor the “power and universal portent” Hart Crane saw in him seven years before when he recognized a poet who could make of sentimentality “a new kind of tragedy.” Again, it would be nice to think such a moment could have saved another poet’s life on board that ship in April 1932.

DVDs of City Lights and The Gold Rush, along with all the other titles in The Chaplin Collection, are available at the Princeton Public Library.