|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 4

|

|

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

|

|

And when is there time to remember, to sift, to weigh, to estimate, to total? I will start and there will be an interruption and I will have to gather it all together again. Or I will become engulfed with all I did or did not do, with what should have been and what cannot be helped.—from “I Stand Here Ironing”

Tillie Olsen, who died at 94 in 2007, was a unique, richly talented writer who led a full, fascinating life and produced a small but highly acclaimed and influential body of work. She was an inspirational figure, not only to those who responded to her as a writer and a speaker/reader, but in particular to members of the feminist movement that gathered force around the time her literary star was rising. The clearest evidence that she had arrived as a writer — a journey that began in the 1930s — was the awarding of First Prize to “Tell Me a Riddle” as the best short story of 1961.

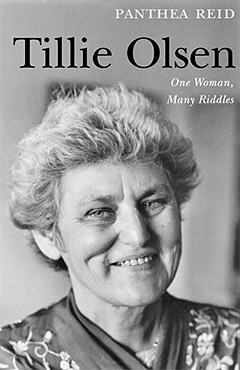

Introducing Prize Stories 1961: The O. Henry Awards, Richard Poirier observes of “Tell Me a Riddle” that its “greatest accomplishment” is its refusal “to be bound by conventional procedures”: “It is as if we were watching reality discover its own rare form of expression.” Poirier’s phrasing anticipates the concept he would develop a decade later in The Performing Self (Oxford 1971). Given his working interest in self-creation, Poirier, who died last August, would have appreciated the way Tillie Olsen’s capacity for self-creation and self-performance in life and in prose is documented in Panthea Reid’s new biography, Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles (Rutgers University Press $34.95). Reid gives a vivid, exhaustive account of how boldly and sometimes deviously Tillie Olsen created, revised, and recreated herself. Reid’s sympathetic, rigorous, and occasionally sternly judgmental assessment of the liberties Olsen took with “reality” provides the biography’s dynamic. The summation of Tillie Olsen during the O’Henry Award period offers a good sample of the book’s style, theme, scope, and character:

“Now she recalled her many lost selves. The Communist zealot was as long gone as the white blouses and red ties of YCL [Young Communist League] uniforms. The shipyard agitator and neglectful mother were as lost as the 79 cent flowered Penney’s dress. The zany cut-up was as discarded as the short skirt and risqué top of the 1945 Labor Day Parade. The sexual tease was as obsolete as the “HOT CARGO” gossip columns. The devoted wife was as forgotten as the nightgowns bought for a postdemobilization honeymoon. The charity activist was as passé as the rakish hats she had worn for press photos.”

The litany ends with reference to the “defiant accuser of the FBI” and the tearful creative writing student, after which Reid asks, “Could she discard the roles of procrastinator, excuse-maker, and victim, and prove her ‘great value as a writer’? Could she write the great novel that would alter the social consciousness of America and the world?”

While Tillie Olsen lived, imagined, but never wrote her novel (the best she could do was to rescue a portion of an abandoned work and publish it in 1974 as Yonnondio: From the Thirties), it’s clear that she made an impression on the “social consciousness of America.” The subsequent chapter titles telegraph the rest of the story: “Ego-Strength,” “Tillie Appleseed,” “Queen Bee,” and “Image Control.”

The book’s last chapter, “Enter the Biographer,” is key because by showing where the biographer is coming from, it humanizes a quest for the truth, the very relentlessness of which may lead some readers to make the mistake of thinking Reid is following a negative agenda. More important, no matter how brilliantly researched and presented the documentation, second- or third-hand accounts can’t equal the experience of meeting Tillie, as it were, face to face. In one instance, when Reid and her husband, Swift scholar John Fischer, both now Princeton residents, spent an evening with Tillie, “John and I left after midnight. As we walked along Laguna Street, something caught our eyes and we looked up to find charming Tillie blowing bubbles to us out of her bedroom window.”

It may be a stretch but keeping in mind Poirier’s concept of the performing self, the wily author may even have been playing out an allusion to her own work. In “I Stand Here Ironing” a baby blows “shining bubbles of sound” and in “Tell Me a Riddle” the mother is “showing us how to blow our own bubbles out of green onion stalks.”

A Wary Subject

Panthea Reid took on the Tillie Olsen case in February 1996, when she was teaching at Louisiana State University and had been moved to write Tillie a letter about her class’s enthusiastic response to “Tell Me a Riddle.” The ensuing correspondence came to an abrupt halt as soon as she said that she wanted to be Olsen’s biographer. Clearly Tillie had second thoughts about being scrutinized by an observer who might perceive flaws or fabrications or reveal secrets. Not until late October 1997, with some help from the youngest of Tillie’s four daughters, did the biographer gain access to her subject.

At Stanford’s Green Library, after her first immersion in “huge boxes filled with papers and notebooks of all sizes” pertaining to Tillie Olsen’s early life, Reid wrote 12 pages toward an article for the magazine DoubleTake. Expecting “a few suggestions,” she showed the pages to Tillie, “who spent the afternoon going over every comma, semicolon, and phrase.” Besides objecting to the “tone,” she “crossed through anything that seemed even slightly critical,” including a reference to her “limited output” and an account of her seven-year-old self’s horrified witnessing of a lynching she’d described in graphic terms during their first conversation. After making some inquiries, the biographer found that Tillie could not possibly have witnessed the lynching or its ugly aftermath. (In a 1999 interview with Anne-Marie Cusac, she no longer claims to have been present, admitting that she read of it “some years later … at the Western Heritage Museum” and that she still has “a recurring nightmare” about it.) After a series of such discoveries, including the covering up of the existence of a first husband, Reid writes, “It dawned on me that her life story was a huge maze.” More than a maze, it was to bring the biographer again and again to the challenge of separating truth from the self-created one’s fabrications. Meanwhile, it had dawned on Tillie that she had reason to be wary of Panthea’s investigative skills. “What a sleuth you are!” she remarked early on, and later, “You ought to work for the FBI.”

Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles is almost certain to cause alarm among the devotees of “Saint Tillie.” There have already been rumblings. In an epilogue, Reid tells of being cut off at a Modern Language Association program that was to be an assessment of Olsen’s life and work. “At that session,” Reid writes, “I argued that we honor Tillie’s legacy by understanding facts rather than perpetuating falsities.” After “listing erroneous but accepted tales about her life” such as the myth that “she was kept out of school until age nine because she was thought retarded” and “that she dropped out of high school to support her family,” Reid was about to go on to Tillie’s later life when she was told that her time was up. Because other speakers had taken much more time, she assumed that she was being silenced by those who wanted to “canonize Tillie.”

Great Lives

Needless to say, biographies of sinners are generally more interesting than biographies of saints. As for biographers, ones like Reid earn our respect by maintaining an enlightened neutrality in graphic contrast to predatory types like Albert Goldman, who savaged Elvis Presley and John Lennon, or Ian Hamilton, who went out of his way to make J.D. Salinger look bad as a pay-back for the legal action Salinger took to scuttle publication of the biography. Classic literary biographies such as Richard Ellman’s James Joyce and Leon Edel’s Henry James do full justice to their subjects, regardless of the negatives revealed.

One of the best biographies I ever read was Barry Paris’s loving, star-struck, if not always flattering life of silent film star and (later) writer Louise Brooks, whose story follows an arc similar to Tillie Olsen’s. Both women gloriously disprove Scott Fitzgerald’s claim that “there are no second acts in American lives.” Just as Nebraska native Tillie became an icon in later life after abandoning for almost 30 years the field in which she seemed destined to succeed (Bennett Cerf and Random House having her under contract), Kansas native Louise became an icon of cinema when she was rediscovered by fans and film critics in the silent classic, Pandora’s Box, 30 years after abandoning stardom in Hollywood.

Great lives challenge and empower an intelligent, determined biographer. Tillie Olsen lived a great life to which Panthea Reid does full justice.

Reading at the Library

Panthea Reid will be reading from Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles at 4 p.m., Thursday, January 28, in the Community Room of the Princeton Public Library. She is also donating copies of Tell Me a Riddle and Yonnondio: From the Thirties to the library’s collection, along with a DVD of Tillie Olsen - A Heart in Action, a film by Ann Hershey.