|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 26

|

|

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 26

|

|

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

|

|

Like him or not, John Wayne, born a hundred years ago this May 26, has become nearly as synonymous with America as the bald eagle, the Stars and Stripes, and the Fourth of July. I wonder how it would be if he were alive at this fraught moment in American history. Imagine this still-venerated movie actor contemplating the damage the current administration has done to the American image he had such an extraordinary and unprecedented stake in. Would he be backing Bush and Cheney right or wrong or would he be trying to help restore America’s credibility by standing up to them and speaking out? His mere presence on the world stage might help put a little more substance into Uncle Sam’s empty suit. Fantasy it may be, but even assuming Wayne would have backed the invasion of Iraq, you have to believe that he’d be speaking out by now against the waste and mismanagement of the war and the neglect of the soldiers and that he quite probably would have agreed about the need for greater troop strength early on when it was suggested by General Shalikashvili, who is said to have learned to speak English by watching John Wayne movies. Could the spin doctors at the White House have spun the Duke? Imagine a world looking for America and finding John Wayne standing there instead of George W. Bush.

But wait a minute. It appears that John Wayne is still very much alive in spite of vital statistics saying that he died on June 11, 1979. It’s true that the same could be said of any number of other Hollywood stars who figuratively live on as long as their movies are shown, but John Wayne has been listed among the living actors in the Top Ten Favorite Movie Stars poll ever since he died. He’s the only one of his generation who can claim factual immortality. The latest Harris Poll of 1,147 U.S. adults, taken last year between December 12 and 18 has Denzel Washington in first place, Tom Hanks, second, with the Duke looming as large as life (larger, it seems) in third place. In 1995, a good 16 years after his death, he was Number 1. In 1994, ’96, ’98, ’99, and 2000, he came in second. He’s never dropped out of the Top Ten, though he did dip to sixth in 2001 and 2002, and seventh in 2005. Will Denzel Washington and Tom Hanks be on the list a year, let alone 28 years, after they die?

Were pollsters to ask me the same question, my Top Ten would be composed of “dead” stars like Humphrey Bogart, Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, and Gary Cooper. Since female stars are counted as well (the only one mentioned in the Harris rankings is alive and well: Julia Roberts), Wayne might not even make the list. He was never a “favorite” of mine. But personal opinion aside, no one casts as long a shadow. By all rights, his politics should date him, but the dimensions of the Wayne phenomenon dwarf the issue of what he believed, never mind how racist or chauvinistic his stance was. He’s become one with his cause now and his cause was the glorification of America. When his sometime co-star Maureen O’Hara helped convince President Jimmy Carter to award him a Congressional gold medal, she said, in effect: “John Wayne is America.”

Again, on July 4, 2007, you have to wonder how proud John Wayne would be of his role as the embodiment of America.

The Key Movies

Herbert Hoover was president when Wayne appeared in his first movie, Brown at Harvard, playing football for Yale. Jimmy Carter was president when he made his last, The Shootist, where he played a dying cowboy. He made more movies (171) and played more leading roles than any other star.

When John Wayne was in disfavor among the young (and most liberal or left-leaning citizens) because of his all-out backing of the Vietnam War and Nixon, students in film classes simply couldn’t “see” him. David Thomson begins his entry on Wayne in his Biographical Dictionary of Film with an account of the time he showed Red River to a large film class. While Thomson’s students would, if prodded, admit to all the movie’s virtues, they couldn’t get into it because Wayne, the man, had come to stand for everything they were dedicated to opposing — even though they’d just been watching Wayne, the actor, play with great force and brilliant craggy intensity an authority figure very like the one they despised in 1971. In fact, Red River previewed the generational combat of the sixties 20 years before it happened, with slight, brooding gay icon Montgomery Clift defying his bullheaded surrogate father.

Another example of the way Wayne was able to creatively adapt his own excesses, angels and demons, can be seen in another of the definitive roles of his life as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers. Once again he’s at his best playing a character resembling the real-life one despised by Thomson’s students as a macho racist tyrant, which would seem to affirm Wayne’s alleged pronouncement that he always played himself. See him in Red River and The Searchers, however, and it’s clear why his gifts as an actor can’t be accounted for so simplistically. True as it may be that Wayne always plays Wayne, what makes his performances in both movies unforgettable is his ability to objectify his own attitudes and develop them within each scripted role to create a character of magnitude and depth. And if you read about him in either of the books I’ve consulted (John Wayne’s America by Garry Wills and John Wayne American by Randy Roberts and James S. Olson), it’s obvious that the man himself was no less complex.

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, one of John Ford’s most appealing movies (also one of his most nocturnal: it has the look of a cowboy noir), you can see Wayne performing with Jimmy Stewart, another tried and true American icon and a more accomplished and versatile actor. Stewart’s passion and humanity make a perfect foil for Wayne’s sheer presence. True, Wayne has the richer role, as the “man” in the title. Stewart plays the relatively mortal individual who goes on to become a U.S. senator thanks mainly to the myth that he (and not Wayne’s character) shot the outlaw, Liberty Valence. Wayne is dead as the movie opens, Stewart and his wife (played with warmth and feeling by Vera Miles) having come back for his funeral. But he’s actually no more “dead” than the actor who figured in all those Harris polls. In effect, he’s the whole movie: the story, the place, the lost time, the lost West, everything. He commits the act that is the picture’s reason for being. He’s deus ex machina, director, central character, and the essence of the film’s elegiac spirit. Although Wayne has been quoted as saying he hates “ambiguity,” he excels in deeply ambiguous roles in all three of the movies I’ve mentioned so far.

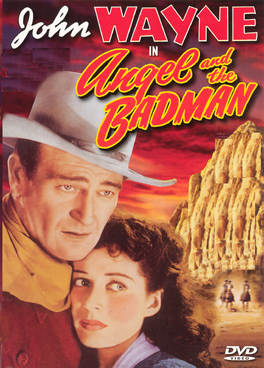

Finally, if you want to see John Wayne at his most appealing, check out Angel and the Bad Man (1947). One of the most remarkable things about this movie, along with Gail Russell’s beautiful performance as “the angel,” is that this essentially “sweet and lovely” story was the first one Wayne picked to produce himself. He also had the good sense to cast Gail Russell, who fell in love with him; her love is obvious and it illuminates the film. While the “bad man” arrives with a deadly reputation, Wayne is able to exploit his gunfighter stature through the sheer power of his presence in dealing with situations where he would otherwise have to violate the Quaker creed of non-violence in front of the young Quaker beauty who nursed him back to health. In the great Leone westerns, Clint Eastwood, for all his mysterious charisma, needs his weapons. John Wayne uses the authority of his presence. He looks the look, speaks the speech, and walks the walk, and when the dust clears, there he is, larger than life — larger than death, for that matter.

All the films discussed here are available on DVD at the Princeton Public Library.