|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 28

|

|

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 28

|

|

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

|

|

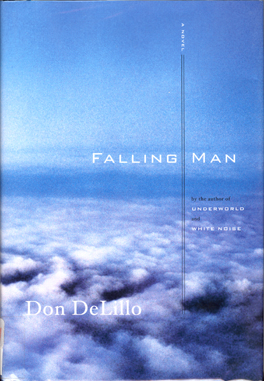

Remember the book (and movie) about June 6, 1944, called The Longest Day? That could also serve as a title for September 11, 2001, which goes on and on and on taking thousands more than the almost 3,000 lives lost in the attacks while helping enable the Bush administration to bring us to the sorry state we’re in today. Until I read Don DeLillo’s new novel, Falling Man (Scribner $26), I’d been wary of books and especially films that extend, in effect, the shadow of 9/11. It could be a simple matter of avoidance or denial or maybe it’s because I doubt anyone could do justice to the magnitude of the tragedy without somehow perversely glorifying it, the way the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen seemed to be doing when he called it “the greatest work of art that is possible in the whole cosmos.”

Ten years before September 11, in his novel Mao II, DeLillo observed that “the more clearly we see terror, the less impact we feel from art.” That statement could serve as an epigraph for his new book as well as an indication of his approach to the event. As Frank Rich pointed out when reviewing Falling Man in the May 27 New York Times Book Review, there are other intimations of 9/11 in DeLillo’s work, not only Mao II but the “airborne toxic event” of White Noise (1987) and the reference to the then-new World Trade Center in Players (1977) as “an unlikely headquarters” for something called “the Grief Management Council.” But then “where else would you stack all this grief?”

Falling Man isn’t an easy read. As I plodded through a relentlessly deadpan narrative in which DeLillo sometimes seems to be deliberately draining the lifeblood from his characters, I kept thinking of other titles: The Manhattan Book of the Dead or the last line from T.S. Eliot’s “Prufrock,” Human Voices Wake Us And We Drown. As Rich puts it, DeLillo makes “disconnectedness … the new currency” with the result that language is “fragmented” and “relationships are a non sequitur” in a setting comparable to “the physical and emotional limbo of a frozen zone.”

In a recent interview on NPR, DeLillo said that writing the book was a “grim responsibility”: “It was the toughest novel I’ve done — not at all in terms of length or research or building structures, but in this emotional sense.” DeLillo isn’t quite clear about what he means by “this emotional sense.” Maybe he means the emotional responsibility involved in making readable fiction out of an abomination. According to DeLillo, the image that inspired the novel is the one it opens with: that of a survivor walking away from the devastation carrying a briefcase belonging to someone else. “I didn’t know who the man was at first,” DeLillo said. “But what I did know was the fact that the briefcase he was carrying was not his and that seemed to suggest a mystery that needed to be solved.”

It’s a rich situation, the shockwave of the catastrophe moving people around, changing lives, restoring marriages, throwing strangers into one another’s arms. In a lesser or more commercially oriented novelist such ideas might be put to superficially exciting narrative use, as DeLillo seems to be doing when he has the man, Keith Neudecker, seek out the owner of the briefcase and begin what appears at first to be a predictable romance between survivors (like the one between Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez in the 1993 film, Fearless). The woman’s name is Florence Givens and she and Keith do have a brief affair, but while the scenes between them carry at least a semblance of emotional immediacy, DeLillo ignores the possibilities a hack novelist would have greedily exploited. The same is true of the other emotionally fertile situation wherein Keith, the disoriented survivor, walks back into his former life with a middle-aged, middle-class wife, Lianne, and young son, Justin. There, too, DeLillo keeps the situation locked in the vise of his “responsibility.” You have the sense that if he could have gotten away with it, he’d have left the characters unnamed, to echo the title: Falling Man, Falling Woman, Falling Child, Falling Other Woman. Additional falling characters include Lianne’s art-historian mother, Nina, and Nina’s art-dealer lover, Martin.

Playing Poker

In spite of my strictly limited knowledge of poker, I found myself thinking of the author of Falling Man as a poker pro playing his hand with consummate craft as he deals cards that could as easily be from a tarot deck. He keeps you guessing. He even works poker into his narrative scheme by having Keith develop a post-9-11 fixation on the game that lands him in Las Vegas, playing for high stakes. DeLillo, as the saying goes, holds his cards close to his chest. Look at the titles he gives to each of the novel’s three parts. Seeing that Part One is titled, “Bill Lawton,” you find yourself looking for a central character with that name. Why not call it “Keith Neudecker”? You have to read 70-plus pages before you learn that when Keith’s son and his playmates look out the window, searching the skies for more planes, they’re talking about an imaginary villain they call “Bill Lawton,” their rendition of “Bin Laden.” The same sleight of hand is at work in the titles for Part Two (“Ernst Hechinger”) and Part Three (“David Janiak”). All three names are like decoys, peripheral gestures that at the same time recreate the sensation (at least for me) of reading the names of the dead in those subsequent issues of the New York Times provided along with photos and brief, often touching bios. In fact, David Janiak is the name of the performance artist who goes about enacting the book’s title image, inspired by the man photographed actually falling from one of the towers. “It could be the name of a trump card in a tarot deck, Falling Man,” Lianne is thinking as she reads Janiak’s obituary.

Like any good poker player, DeLillo occasionally shows his hand by seasoning the narrative with insights into his rhetorical strategy, as when Keith chides his son for talking in monosyllables, saying, “I don’t care. You can talk in the Inuit language if you like. Learn Inuit. They have an alphabet of syllables instead of letters. You can speak one syllable at a time.” While DeLillo’s style in this book may not be monosyllabic, it does impose the monotone quality I had in mind when I referred to the deadpan narrative. The effect, particularly in the dialogue, suggests the labored sound of a work in progress, as if people were rebuilding language and learning how to communicate all over again in the echoing vacuum of the longest day ever, 9/11’s endless aftermath. Another schematic insight comes when Lianne tells herself, “Stand apart. See things clinically, unemotionally …. Measure the elements. Work the elements together. Learn something from the event. Make yourself equal to it.”

Every now and then, seemingly in spite of himself, DeLillo allows touches of beauty and poetry to slip into the narrative, as when he compares the laundry room in Lianne’s building to “a monk’s cell” in which the dryer and washing machine are “a pair of giant prayer wheels beating out a litany.” This lovely, ingenious simile stands out from the tenor of the novel like a fragment of exotic music, as if someone somewhere had turned on a radio in the middle of what could well be another confrontation between Lianne and a woman she’d attacked in a previous scene. “The question was whether a look would lead to words and then what.” The question is also what in this tense context can justify that elaborate simile? It almost seems that DeLillo couldn’t resist giving the hungry reader a taste of poetry in what has been a no-man’s land of taut, impersonal prose.

Moby’s Hymn

If you want to hear music that transcends 9/11 even as it’s haunted by the nightmare, listen to Moby’s album, 18, which was released in early 2002. Although Moby, a.k.a Richard Melville Hall, says that he wrote the songs a year before the attack, he clearly must have chosen and arranged the music after the event because 18 is nothing less than a hymn for the loss on 9/11 and a healing elegy for the stricken city, especially in songs like “We Are All Made of Stars” (“People they come together/ people they fall apart”), “Great Escape,” “Signs of Love” (“I fly so high/And fall so low”), and “Sleep Alone” (“At least we were together, holding hands, flying through the sky”). Moby also has an intimate relationship with the longest day. He was born on September 11, 1965.