|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 24

|

|

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

|

O Nora! Nora! Nora! I am speaking now to the girl I loved, who had redbrown hair and sauntered over to me and took me so easily into her arms and made me a man.James Joyce to Nora Barnacle, August 7, 1909

I know and feel that if I am to write anything fine or noble in the future I shall do so only by listening at the doors of your heart.James Joyce to Nora Barnacle, August 19, 1909

It all began with a pick-up. James Joyce was on his way down Nassau Street (the one in Dublin, that is) when his eye was caught by “a tall young woman, auburn-haired, walking with a proud stride,” according to Richard Ellman’s James Joyce (1959). When Joyce spoke to Nora Barnacle, she “answered pertly enough to allow the conversation to continue.”

Nora had come to Dublin from Galway and was working as a chambermaid at a “slightly exalted rooming house” then called Finn’s Hotel (you can still see the faded lettering on the rear of the building). A June 14 meeting was agreed on, but Nora didn’t show up. After Joyce sent her a disappointed note expressing the hope that she would make another appointment (“if you have not forgotten me!”), they finally got together on June 16, 1904. What actually happened on this “first date” — the beginning of a relationship (they were not legally married until 1931) that lasted until Joyce’s death in January 1941 — has been hotly debated over the years. Judging from a December 3, 1909, letter from Joyce that was suppressed until 1975, the encounter was not altogether platonic.

Although some ten years passed between that first rendezvous and the time Joyce actually began writing Ulysses, the day he chose to set it on was, as Ellman observes, not only an “eloquent if indirect tribute to Nora,” but was also the date “he entered into relation with the world around him and left behind him the loneliness he had felt since his mother’s death.”

The worldwide celebration of June 16 as Bloomsday is a recognition of the scope and literary stature of Joyce’s tour de force, and, above all, it’s a tribute to the novel’s humanity, especially as embodied by Leopold Bloom and his no-nonsense, Nora-inspired Molly.

The Dismissive Muse

How fortunate for literature that of all the women he might have approached that day on Nassau Street, Joyce picked one “who would have no truck with books,” according to Sylvia Beach’s memoir Shakespeare and Company (1959). Nora tells Sylvia “that she hadn’t read a page of ‘that book’” and “nothing would induce her to open it.” As the publisher of Ulysses, and one of its staunchest admirers, Beach knew well enough that it was “quite unnecessary” for Nora to read Joyce’s magnum opus, for “was she not the source of his inspiration?” Beach makes clear that while Nora used to tell her “she was sorry she hadn’t married a farmer or a banker, or maybe a ragpicker, instead of a writer,” it was “a good thing for Joyce” that they found each other: “His marriage to Nora was one of the best pieces of luck that ever befell him.”

Arguably the second most important woman in Joyce’s life as a writer, Sylvia Beach had come to Paris by way of Princeton where her father had been for 17 years pastor of the First Presbyterian Church (she’s buried in Princeton cemetery). Legend has it, by the way, that Beach and her partner Adrienne Monnier presided over the first ever celebration of Bloomsday in 1929. The more elaborate inaugural event took place on the 50th anniversary, June 16, 1954, when a group of Dubliners led by novelist Flann O’Brien assumed the roles of characters in the novel and hired horse drawn cabs to take them along Bloom’s route through the city.

Joyce is Fun

But you might not think so if you happened on the full-page ad in Sunday’s New York Times Book Review from the Teaching Company in Chantilly, Virginia, which offers intimidated readers a way to “Examine the Multilayered Pleasures of James Joyce’s Modern Epic … in 24 Vibrant Recorded Lectures.” Yes, folks, if you feel intellectually challenged by “a book whose pleasures you have always wanted to savor, but never quite worked yourself up to reading,” just tune in to Professor Emeritus James A.W. Hefferman (a Princeton Ph.D. wouldn’t you know), who “presupposes no special knowledge of literature or James Joyce” in his listeners. Not surprisingly, there’s no money-back guarantee should the course fail to help you work yourself up to the realization that Joyce’s novel is actually a “surprisingly accessible work that offers near limitless rewards to its readers.” The good old-fashioned red-lettered come-ons — “Act Now!” “Order Today!” “Save Up to $185!” — would no doubt amuse an ad canvasser like Mr. Bloom, who shares his creator’s eye for such things.

Discovering Joyce

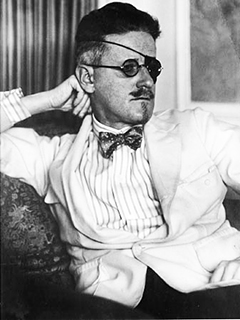

So how is it that James Joyce spoke to a 17-year-old who would ordinarily rather play baseball than read a book and who, when he did read, was more attuned to Mad Comics and Mickey Spillane than serious literature? Certainly it helped to live in a household where you could casually come across a copy of the Signet paperback of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man with its intriguing cover imagery of a sailing ship, church spires, a scantily-clad girl bathing in a stream, and on the back an image of the author looking like a literary pirate, complete with eyepatch.

Portrait proved to be the most intense reading experience of my life to that point, from the magical opening about the “moocow and baby tuckoo” to a mercilessly protracted description of the agonies of hell that harrowed my teenage soul with visions of eternal damnation. No less powerful was Stephen’s “outburst of profane joy” when during his already madly exalted walk along Sandymount Strand he sees a solitary girl with her skirt hiked up, bathing “alone and still, gazing out to sea.”

In college, having “worked myself up” for Ulysses by reading the stories in Dubliners, I took the plunge, bought a copy of the third U.S. edition at a used bookshop in New York, and attacked it with a ballpoint pen, shamelessly scattering exclamation points and question marks in my wake. When the sheer fun and flavor of the language and the overwhelming sense of its magnificent limitlessness (as opposed to the Learning Company’s “limitless rewards”) could no longer be contained, some friends and I would pass fragments of the text back and forth like a secret language of occult phrases such as “Milk for the pussens!” (“Mrkgnao! the cat cried”) or “Out of that, Tatters!” or “Blimey it makes me kind of bleeding cry, straight, it does, when I thinks of me old mashtub what’s waiting for me down Limehouse way.”

Is Joyce fun? Twice now I’ve taken Volume 2 of the Odyssey paperback edition of Ulysses on flights to the U.K. The only problem with reading the hallucinatory vaudeville of the Nighttown sequence at 30,000 feet is it has you laughing out loud so much that the flight attendants start giving you worried looks. And you get more looks when you come to Molly’s 40-plus-page rhapsody, for how can you read it without moving your lips, speaking those words, not all of which are acceptable in polite in-flight society? Thanks, Nora! Once again, how lucky for us that it was you James Joyce spotted that day on Nassau Street.

Being There

If you visit Dublin after your first taste of Ulysses, every day is Bloomsday. You hit the Martello Tower at the crack of dawn, where the narrative begins, then the Bloom residence at 7 Eccles Street, where Poldy begins the “gentle summer morning” of June 16 by fixing breakfast for Molly, and serving it to her in bed. Then you can walk on Sandymount Strand and have epiphanies like Stephen’s with the barefoot maid in the stream, or you can hike across Howth Head where Leopold and Molly made love. Around midnight. when you head toward Amiens Street Station on your way to the site of Nighttown and everything is in a sort of semi-intelligible mist, you can believe literature is near to a divinity brooding over the city you’re finding your way through as if you were just another character prowling about in the imagination of the man who wrote the book.

Later that summer on a rainy day in Zurich I made a pilgrimage to Joyce’s grave. A man in a mackintosh like the one who haunts Ulysses showed me to the gravesite and then discreetly disappeared. In those days, there was nothing to be seen but a plain black headstone bearing only his name and his dates (1882-1941).

You can get an idea of the events taking place this June 16 by googling Bloomsday. Friday’s New York Times ran a story on the various Bloomsday events in Manhattan and Brooklyn (“Stream of Conviviality for Leopold Bloom’s Day”).