|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 12

|

|

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

|

|

“No piece was easy, but each fell finished, in its shroud of print, into a book-shaped hole.”

In the two lines preceding those brutally unsparing words in a poem he calls “Spirit of ’76,” John Updike (1932-2009) speaks of seeing “clear through to the ultimate page,/the silence I dared break for my small time.” Balzac himself might admire the bloody but unbowed tenacity of an author composing a self-portrait of his own death, as Updike does in poems like “Oblong Ghosts” and “Needle Biopsy” in the March 16 issue of the New Yorker. It’s just the sort of grand heroic flourish a Balzacian artist would perform — indomitable, determined to take verbal possession of the terms of his fate, fully engaged in his art to the end. This ten-poem coda to the book of his life is pure Updike, the last, perfect fall of the finished piece. The line that concludes “Spirit of ‘76” — ”at ceremony’s end, my wife points out/I don’t know how to use a finger bowl” — may be a long way from John Keats’s farewell line, “I always made an awkward bow,” but it’s perfectly in character for the poet articulating his doom in “Needle Biopsy” (“The needle, carefully worked, was in me, beyond pain,/aimed at an adrenal gland. I had not hoped/to find in this bright place, so solvent a peace./Days later, the results came casually through:/the gland, biopsied, showed metastasis”).

The issue of the New Yorker containing those poems was apparently timed to coincide with the week of John Updike’s birthday, which is today, March 18. He would have been 77. He died on January 27.

Updike’s death provoked a media tribute worthy of a national hero. You can hear an echo of Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man in the headline the New York Times reserved for the occasion: “A Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class Man.” The Times sounded the same note in 1988 on the occasion of Raymond Carver’s death with an obituary titled “Writer and Poet of the Working Poor.” When Norman Mailer died in November 2007, on the other hand, it was “Towering Writer With a Matching Ego,” and for William Styron in November 2006, the Times head carried no comment, perhaps due to the dictates of page lay-out or maybe because Styron couldn’t be so easily and succinctly categorized.

At one time or another over the years, I’ve connected with works by Mailer, Styron, and Carver. This hasn’t been the case with Updike. I’ve sampled embarrassingly little of his immense store of fiction. As much as I admired Rabbit Run (1960) and The Poorhouse Fair (1959), I couldn’t get past the dense thicket of purple prose in the opening pages of The Centaur (1963). The same thing happened with novels such as A Month of Sundays (1975) and Roger’s Version (1986). Even the subsequent Rabbit books never really came together for me. Every other year or so I’d pick up the latest Updike at the library with the same result. As I’ve since discovered, reading books to review encourages the sort of sympathetic patience I was unable to bring to some of Updike’s major works. If I went back to them now, I know I’d have a clearer appreciation of his stature.

The Considerate Reviewer

Given all these reservations at a time when universal acclaim has been the norm, why, then, am I writing a column on Updike’s birthday? One reason is my enjoyment of his non-fiction pieces, which have given a special glow to the New Yorker over the years. I will miss his contributions to Talk of the Town no less than his book reviews. The example he’s set by writing so wisely and graciously about other writers should be an inspiration to any reviewer and has made me determined to write as honest a summation of my thoughts about Updike as I can at this time. I can’t imagine a more enlightened set of rules for reviewers than the one he outlines in the introduction to Picked Up Pieces (1975). Paraphrased, the rules include the obligation to try to understand what authors wish to do, and not to blame them for not achieving what they didn’t attempt; to give enough direct quotation — ”at least one extended passage” — of a book’s prose so that the readers of the review can form an impression of their own; to provide a quotation from the book along with one’s own description, rather than proceeding by “fuzzy precis”; to “go easy” on plot summary, and not to give away the ending; and if the book is judged deficient, to cite “a successful example along the same lines, from the author’s ouevre or elsewhere,” and then to try to understand the failure, and make sure it’s theirs and not yours.

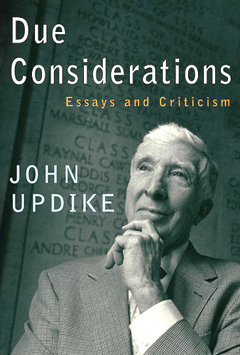

Updike also mentions the importance of never accepting for review “a book you are predisposed to dislike,” or are “committed by friendship to like.” If you’re a regular reader of the N.Y. Times Book Review you’ll know how rarely Updike’s principles are heeded, something he himself usually does. In the introduction to his last collection of non-fiction, Due Considerations, Essays and Criticism (2007), he even laments his own “testy quibbling,” going so far as to ask himself, “Why was I such a rudely squirming student in the classrooms of Denis Johnson’s and Norman Rush’s teacher-heroes, and sympathized so stingily with their romantic and spiritual dilemmas?”

Due Considerations offers numerous characteristically stylish, amusing glimpses of Updike’s writing life, including his psychology of book reviewing, which “felt physically close to writing a story” with “a similar need for a punchy beginning, a clinching ending, and a misty stretch in between that would connect the two.” Then there’s his account of first reading Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady “as a young man of twenty-three in New York City,” where he would “catch the subway at Eighty-sixth Street and stare into the closely printed pages” of the Oxford Classics edition “for the seven stops and twenty minutes it took to arrive at Times Square.” On the way back, at rush hour, “I usually had to stand, swaying, jostled, gripping a porcelain loop while I buried my head, ostrichlike, in the accreting sands of James’s tale as it made its leisurely way from England to Paris to Florence and Rome and back to England,” thus “dulling the indignities of my twice-daily passage with a fiction so refined, so aloof in its voice and milieux from the underground congestion of the American metropolis.”

Updike’s Last Interview

If you access the online New York Times obituary, you can watch last fall’s in-depth hour-and-a-half conversation between Updike and former Times Book Review editor Charles McGrath at the Times Center in New York. Updike manages the situation with patience and great charm, particularly when fielding questions from the audience about perceived lacks in his own work (not enough character development, an excess of style at the expense of content). That the event took place on October 28, 2008, only three months before he died makes his thoughtfulness, wit, humanity, and eloquence all the more impressive. It’s stunning to think that he’s taking on so public a challenge a mere week before he wrote and dated the poem “Oblong Ghosts” (“It seems that death has found/the portals it will enter by: my lungs”). Finally, there’s the moment when this self-confessed “old-fashioned Democrat” reveals how pleased and excited he is by Barack Obama, a “once in a lifetime candidate,” the “graceful, thoughtful” man who would be elected president a week later.

The closing sentence of Due Considerations, from Updike’s contribution to NPR’s series “This I Believe,” suggests that he already had his eye on the ultimate page: “We are part of nature, and natural necessity compels and in the end dissolves us; yet to renounce all and any supernature, any appeal or judgment beyond the claims of matter and private appetite, leaves in the dust too much of our humanity, as through the millennia it has manifested itself in arts and altruism, idealism, and joie de vivre.”