|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 44

|

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

|

|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 44

|

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

|

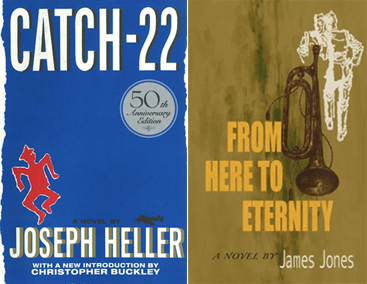

Deuces Wild: A Tale of Two Modern ClassicsStuart MitchnerFifty years ago this November 11, Simon and Schuster published Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 to wildly mixed reviews; sales were middling. Sixty years ago in February of 1951, Scribners published James Jones’s From Here to Eternity to the sort of sales and reviews writers dream about. The Catch It makes some kind of senseless sense that when you put Catch-22 into the mix, things go a bit crazy. Yes, the publication date was November 11, but in Joseph Heller’s introduction to the 1994 edition of the novel, he says the New York Times reviews appeared two weeks after the publication date when in fact they actually appeared a month before, on October 22 and 23.The naming of the book has a quirky history all its own. Heller intended it to be Catch-18, and the first chapter appeared under that title in 1955 in the paperback anthology New World Writing. But in 1961, the similarity to a recent best-selling novel by Leon Uris (Mila 18) forced the author and his agent, Candida Donadio, to do a numerical version of musical chairs. Catch-11 was rejected because of the recent hit film, Oceans 11, and Catch-17 clashed with another high-profile film, Stalag 17. The ultimate and decisive advantage of Catch-22 was that snappy duplicate digit. In any case, the word would become, like Nabokov’s “nymphet,” a standard dictionary item, defined as “a situation in which a desired outcome or solution is impossible to attain because of a set of inherently illogical rules or conditions,” or “a situation or predicament characterized by absurdity or senselessness.” The Modern Library’s list of the greatest English language novels of the twentieth century has Catch-22 at number 7, as determined by a review panel. When the reading public was polled, the book ranked 12th, and would actually have been 5th if you discount the votes of the Ayn Rand and L. Ron Hubbard cliques (Rand’s four books are in the top ten and Hubbard holds three spots). Meanwhile, From Here to Eternity doesn’t appear on the public’s top 100 at all and comes in at number 62 on the panel’s list. What really put Catch-22 on the map was the timing of its appearance. The novel might not have sold all that well in hard cover, but when the Dell paperback came out in 1962 plastered with rave notices like Nelson Algren’s (“not merely the best American novel to come out of World War II; it is the best American novel to come out of anywhere in years”), it went on to sell over eight million copies in the U.S. and two million in the U.K. While novels such as Norman Mailer’s Why Are We In Vietnam? were consciously styled to express the period, Catch-22, like Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove and the Beatles, actually came to stand for the sixties. While there’s no way to prove it, readers in the fifties are unlikely to have been as attuned to this crazed, irreverent performance, with its dark, vaudeville-style mockery of the hallowed and triumphant American military. Shock and Outrage From Here to Eternity has little to do with any period stereotype of the fifties. It’s too large and rule-breaking, has too much mass and force, sexual energy, and raw proletarian eloquence. Like Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (another classic from 1951), Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) and William Burroughs’s The Naked Lunch (1959), it’s a domain unto itself. That it should flourish in the fifties is no surprise. What better foil for a book of such power than the Eisenhower era? And though it may seem a piece of straight-faced realism next to Catch-22, the negative picture it paints of the American military is, in its way, more damning than Heller’s black comedy send-up. The most shocking thing in a book packed with shocks was not the language or the sex, according to the February 26, 1951 New York Times review by Orville Prescott, but the “gigantic power of a military organization” being used “to break one individual standing up for his rights.” Prescott is particularly repelled by (shades of Abu Ghraib) “the sadistic tortures inflicted in the punishment ‘stockade,’” which he says will leave “sickened and enraged readers wondering how much American Army practices duplicate those of totalitarian nations.” Known as “the dean of American book reviewers” in his day (1942-1966), Prescott rarely showed much tolerance for literary innovation. Yet his reviews of both From Here to Eternity and Catch-22 reveal a grudging appreciation of the qualities that make each book remarkable. I expected Prescott to be scolding Jones for being sloppy, brutal, and verbose, not to mention fussing about his groundbreaking use of the f-word. After warning that many readers will be “outraged” and that “it’s possible to dislike this book heartily,” he admits finding it “impossible … to ignore its dynamic punch” — in fact, “its narrative power [is] as exciting as a sock on the jaw.” (If you think getting socked on the jaw is exciting, that is.) Catch-22 prompts similar language from Prescott (it will “outrage as many readers as it delights”) and has him squirming as he tries to get a handle on the thing: “It is not even a good novel. It is not even a good novel by conventional standards.” After that weird double-clutch (itself so Catch-22), he delivers a statement of such breathtaking absurdity it might have come from the pages of the book: “But there can be no doubt that it is the strangest novel yet written about the United States Air Force in World War II.” Opening Sentences This is how Catch-22 begins: “It was love at first sight. The first time Yossarian saw the chaplain he fell madly in love with him.” This is how From Here to Eternity begins: “When he finished packing, he walked out on to the third-floor porch of the barracks brushing the dust from his hands, a very neat and deceptively slim young man in the summer khakis that were still early morning fresh.” If you’ve seen the 1953 movie, you’ll instantly picture Montgomery Clift as Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt in that classic opening sentence, a piece of casting so perfect that it’s hard to believe Jones didn’t create the character with Clift in mind. His opening strikes a conventional note that evokes a solid novelistic tradition, a suggestion of Hemingway in the cadence (see the first sentence of For Whom The Bell Tolls), while Heller takes a cliché of romance and connects it to an amusingly unlikely subject. Hemingway may be somewhere on the premises, but as you get into the nutty dialogue you’re reminded more often of the verbal rhythms of Groucho Marx. The Presence of the Book Design, content, and author coalesce magnificently in the early hardcover edition of From Here to Eternity sitting on my desk. The book has as much force and presence as it did in the summer of 1957 when I bought it in a Fourth Avenue bookshop: James Jones glaring, pure menace, in that striped, off-the-shoulder t-shirt in what may be the most compelling author photo ever, even counting the one of Truman Capote lounging on the back of Other Voices, Other Rooms. Wrapped in the original khaki-colored dust jacket, with the image of the bugle, Prewitt’s bugle, adjacent to the orange letters of the title, here’s a substantial (861 pages) and inviting fact of book life that Kindles and Nooks and e-books will never be able to give you. I should admit that my first reading of Jones’s novel was not the hefty hard cover but the Signet paperback; the same admission holds for Catch-22, which Simon and Schuster has just released in a 50th Anniversary Edition, with an introduction by Christopher Buckley. Both books are available in e-book editions, if that’s your preference, and Open Road Integrated Media is offering a digital version of From Here to Eternity containing explicit references to gay sex and a number of four-letter words that Scribners convinced Jones to drop from the original text. Open Road also plans to publish nine other titles by Jones, one of which, To the End of the War, has never been published in any form. Although each of these books would be high on my personal list of 20th Century American novels, From Here to Eternity would outrank Catch-22 if only because reading it amounted to a literary coming of age. Jones’s elaborate, shimmering description of the layers of sound coming from the bugle when Prewitt plays Taps may have been the first time I realized that writing could be beautiful and exciting in and of itself. Nor had I ever read anything like the description of how it felt to hear Django Reinhardt’s “hard-driven swiftly run arpeggios, always moving, never hesitating, never getting lost and having to pause to get back on, shifting suddenly from the set light-accent of the melancholy jazz beat to the sharp erratic-explosive gypsy rhythm that cried over life while laughing at it.” |