|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

|

|

|

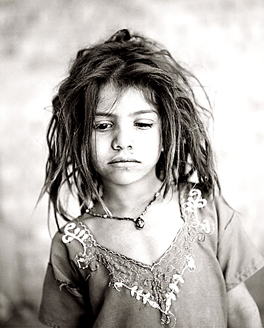

TWO GIRLS FROM “BELOVED DAUGHTERS”: Two of the most haunting faces from Fazal Sheikh’s exhibit at the Princeton University Art Museum suggest the beauty and sadness to be found in “Beloved Daughters.” The exhibit, which runs through January 6, 2008, has been made possible by Jane P. Watkins. Fazal Sheikh’s projects, “Moksha” and “Ladli,” received support from the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris. Online editions can be viewed at www.fazalsheikh.org or purchased in book form at the museum shop.

| |

A friend traveling in India once wrote to me that I would need “500,000 tons of pure and indifferent love of humanity” if I hoped to survive that country. During the six months I spent there, his advice seemed to work for me, if only as a sort of subliminal code opening the way to a supremely positive experience. It didn’t work so well during scenes like the one at Mughal Sarai, a railway junction in Uttar Pradesh where my feelings became the opposite of pure and indifferent. Love’s got nothing to do with it when “humanity” is a crazed mob rioting for places on too few third-class carriages on a train bound for the holy city of Benares.

The friend who gave me that advice had lost touch with it himself by the time I found him in Calcutta, where he’d taken to his bed, unable to deal with the City of Dreadful Night. A few months later, however, when a member of the Peace Corps was declaiming melodramatically on the misery and hopelessness of India, my friend said, “I like the hopelessness.” He wasn’t being perverse; what he really meant was that he loved the country in spite of the fact that the hopelessness had nearly driven him mad, and that it was impossible for him to separate the misery from the beauty in a phenomenon as vast and unfathomable as India.

A version of that phenomenon can be experienced and debated in the Princeton University Art Museum’s powerful new exhibit, “Beloved Daughters: Photographs by Fazal Sheikh.” I don’t use the word “powerful” lightly. These images and the stories behind them challenge the usual art-review terminology. This is no more a “show” than the riot at Mughal Sarai was. Unless you walk through it without reading the commentaries and narratives posted along the way, the subject matter is going to force you into an aesthetic impasse where any appreciative response seems inadequate in the face of the sheer viciousness, injustice, and inhumanity looming behind the images in “Beloved Daughters.” However much there is to admire in the artistry and the concept of the project, what you’re admiring lies in the shadow of an abomination. The essential information is that the first part, “Moksha” (meaning heaven), is composed of pictures taken in the city of Vrindavan, most of them of the dispossessed widows who go there to seek refuge and live out their lives as devotees to Krishna The second part “Ladli” (or “beloved daughter”) is made up of portraits of women of all ages who have suffered the consequences of being born into a society in which they are worse than “second-class citizens.” The fact that all of the 150 photographs are black and white emphasizes the haunting beauty of Indian surfaces, structures, objects, animals, forms, and faces while sustaining the somber message. Otherwise, the inescapable brilliance of Indian colors would dazzle and distract you much the way they do when you’re actually traveling there. In that sense, I find myself in the same position I’m in when people ask me about my time in India. Just as it’s too easy to say I enjoyed and admired an exhibit whose message is so dire, it’s too easy to say that “I loved India,” that it was the most rewarding and in every way fulfilling journey of my life. It’s always necessary to acknowledge at some point an awareness of the unlovely and unlovable underlying reality. A whole generation began loving India in the 1960s, with Ravi Shankar and the Beatles and the San Francisco renaissance leading the way. It was all sitars, incense, and Nehru jackets as people throughout the Western world succumbed to the colors, the music, the mysticism and mystery, all that was exotic and exciting, while inevitably and necessarily remaining in denial about the inconceivably ugly human truth at the heart of the subcontinent.

Obviously, to “enjoy” or “appreciate” an exhibit like this, you have to make some moral adjustments. You also have to assume that the title is not meant to be taken ironically or ambiguously, given what happens to “beloved daughters” in a country where, according to a survey quoted in a posted note, “500,000 girls are aborted every year,” which would mean that in 20 years, so they estimate, ten million beloved daughters have been “terminated at or before birth.” The daughters who survive are sold, abandoned, exploited, abused, and murdered, among other things. The storyline is graphic: from domestic slavery and forced prostitution, to wife-murderers who are never brought to justice, and female children who are abandoned or killed. Of all the faces to be seen here, the only woman who revealed even the vestige of a smile was Afshana, seen holding a diploma in her hand in a photograph not taken by Mr. Sheikh. For her arranged marriage, the dowry was a black and white TV, a refrigerator, some gold, and other household items. After the agreement had been sealed, the husband asked for a motor scooter to be added, but was refused. Whether or not that point of contention was responsible, Afshana was abused by her husband and in-laws and shortly after a visit to complain of it to her mother, she was murdered, burned to death.

A Beautiful Day

The opening day of “Beloved Daughters” saw the celebration of at least two weddings at the nearby University Chapel, where two brides posed for pictures with mates they had presumably chosen of their own free will. The weather was about as good as it gets. But coming out of the exhibit, it was hard not to be thinking, “Just like the weather on September 11.” Or to be tagging “beautiful day” with an asterisk and putting another one after “Till death us do part.” Of course you can be positive and think how lucky you are to live in a civilized country — until you remind yourself that right now, in the fall of 2007, our own “beloved sons and daughters” are being blown up, murdered, burned, disfigured, and mutilated in Iraq, not to mention what the Sunnis and Shias are doing to one another. Not to mention Darfur, Myanmar, and on and on as “humanity” keeps thwarting our “pure and indifferent love” of it. As much as you may want to focus on the aesthetic pleasures to be found in “Beloved Daughters” (and they are plentiful), it’s hard not to notice the people gasping and talking to themselves as they read stories that are still shocking no matter how much you’ve heard about the plight of women in India and the Third World, or read of it in Nicholas Kristof’s columns in the New York Times, or saw it dramatized in Deepa Mehta’s fine film, Water, where a widowed child bride is sent to live in a commune for widows not unlike the subject and setting of “Moksha.”

Emmet Gowin’s Lesson

Fazal Sheikh is a Class of 1987 Princeton alumnus who has worked with displaced communities in South Asia, Africa, and the Americas. At Princeton he studied photography with Emmet Gowin and credits his teacher for pointing him in a direction he could follow. Quoted by Photography Curator Joel Smith in the exhibit brochure, he says that his inclination was “to handle the image with care. Some people would argue that it’s inappropriate to do that when you’re dealing with a raw, unresolved, political issue — but … I felt what Emmet would say: if you care about something, you have to render it in a way that shows that, and encourages people to want to know more.”

I’m not sure how much more the dazed viewers will want to know after seeing “Beloved Daughters,” but they will be moved, “sadder and wiser,” and they will want to see more of Fazal Sheikh’s work. Complete online editions of Moksha and Ladli can be viewed at www.fazalsheikh.org or purchased in book form at the museum shop.