|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

|

|

More than anyone else of his time, Mailer is implicated, in every sense of that word, in the way we live now …. At his best, he seeks contamination. He does so by adopting the roles, the styles, the sounds that will give him the measure of what it’s like to be alive in this country.Richard Poirier

Norman Mailer, who died Saturday at 84, deserves a more thoughtful headline for his incredible career than the one chosen by the New York Times for an otherwise worthy obituary (“Towering Writer with a Matching Ego”). As Richard Poirier has pointed out, nearly all of Mailer’s writing depends not so much on “the famous Mailer ego” as on “a degree of self-fragmentation and dispersal” that allows him to enter fully into his subject. In his prime, Mailer didn’t just take the measure of “what it’s like to be alive in this country,” he became, or at least attempted to become, this country.

“I’ve been angry at America most of the years of my life,” Mailer admitted in one of his last public appearances, on June 27, at the New York Public Library. “But I’ve always been in love with America. It’s as if I’m married to America.” Like Kurt Vonnegut, who died in April, he sees the Bush administration’s misadventure in Iraq (“the worst war we’ve ever been in”) as grounds for divorce. His analogy is that “one’s country is one’s mate” and that the invasion of Iraq is comparable to your mate “cheating” on you and entering into “a really foul relationship.”

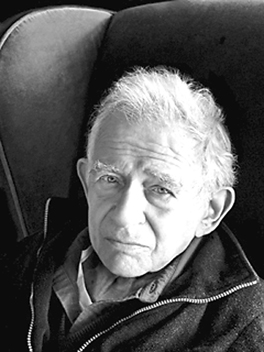

In the segment from the June 27 appearance, which can be seen on YouTube (“Norman Mailer — Iraq and the American Right”), Mailer looks frail; he’s obviously ailing, his voice is cracking, and while he may not be the cocky battler of old poised on the edge of his seat as he sizes up the “talent in the room,” it’s moving to see him still holding forth, still in touch with the themes that make it hard to imagine life in the last half of the 20th century without him. It’s also hard to conventionally mourn this Jersey-born phenomenon. You may as well weep for a comet. On a domestic level, you could compare him to some flamboyant distant relative with a penchant for yearly surprise visits that invariably gave an exciting lift to ordinary life, and made the idea of being a writer more challenging and desirable. But then there were those catastrophic call-911 occasions when he brought along a convicted killer he’d just liberated from Death Row, or when he stabbed his wife, or started a playful political sparring match with Uncle Fred that turned ugly and violent.

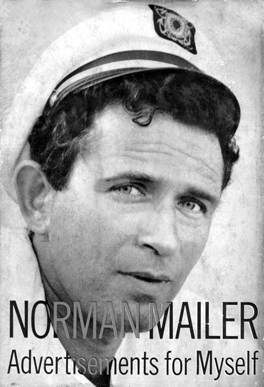

My relationship with Norman Mailer began with Advertisements for Myself (1959), the daring, ingenious, bellicose collection that turned his career around. At 25, he’d been the first to win big in the war novel lottery with The Naked and the Dead (1948), which was both a best-seller and critical success. His next two novels, Barbary Shore (1951) and The Deer Park (1955), seemed lost causes by comparison. With Advertisements he put himself on the map, establishing the contentious, confessional persona first aired in his Village Voice columns and later amplified in venues like Esquire, Harpers, and the Atlantic. Though it was written in the late 1950s, Advertisements swung with the spirit of the sixties. Howl and On the Road looked ahead to the turbulence of that decade, but Advertisements was somehow already there. Mailer’s voice is also very much there, as is the Mailer ego, from the first paragraph on: “Like many another vain, empty, and bullying body of our time, I have been running for President these last ten years in the privacy of my mind….The sour truth is that I am imprisoned with a perception which will settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time.”

Mailer may not have accomplished his revolution, but no other 20th-century American writer I can think of came as close and no other writer has matched the range and passion of his six-decade adventure. As his sometime mortal enemy Gore Vidal has written, he could be “more bold, more loud” and put on “brighter motley and shake more foolish bells” than any of his peers while remaining “a force and an artist” whose faults ultimately add to the “sum of his natural achievements.”

Mailer was an indispensable voice, no matter what he was discussing: drugs or sex, politics or American culture, presidents, boxers, or murderers. He took more risks and covered more ground than any of his contemporaries. As a novelist, he was a prose superman who sometimes soared over the top into a purple no-man’s-land; as an observer covering some of the major events of his time, he was both stylish and cuttingly acute, a freeswinger who could go to the heart of a scene or illuminate the central players with a novelist’s flair. Mailer’s command of narrative, metaphor, and character made his account of any event the one that mattered most. Mention the so-called non-fiction novel and people automatically cite Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1965) or the work of Hunter Thompson and Tom Wolfe, but Mailer was there as early as the summer of 1960 when he not only made the protagonist of his real-life narrative a presidential candidate but at the same time may have contributed to the making of history. There’s some truth in Mailer’s boast that his portrait of candidate John Kennedy in Esquire (“Superman Comes to the Supermarket”) helped elect the man. In fact, I was one of those whose vote was decided by that article. Having grown up in a Republican family and a Republican state, with Time magazine’s negative cover story on the Kennedy family fresh in my mind, I hadn’t decided who to vote for until Mailer transformed Kennedy into the hero of a real-life work-in-progress. As he admits in The Presidential Papers (1964), which contains the Esquire article, his purpose was to portray Kennedy as a fascinating, charismatic, electable hero: “the hipster as presidential candidate,” “the edge of the mystery,” the matador on the shoulders of the crowd, football hero, campus king, “the matinee idol, come to the palace to claim the princess,” a war hero, a man who had “lived with death” and carried himself “with the poise of a fine boxer,” not to mention choosing to marry “a lady whose face might be too imaginative for the taste of a democracy.” And all this was only the build-up to a still more compelling portrait:

“His personal quality had a subtle, not quite describable intensity, a suggestion of dry pent heat perhaps, his eyes large, the pupils grey, the whites prominent, almost shocking, his most forceful feature: he had the eyes of a mountaineer. His appearance changed with his mood, strikingly so, and this made him always more interesting than what he was saying …. [Then] he would look again like a movie star, his coloring vivid, his manner rich, his gestures strong and quick, alive with that concentration of vitality a successful actor always seems to radiate …. Although they were not at all similar as people, the quality was reminscent of someone like Brando … because, like Brando, Kennedy’s most characteristic quality is the remote and private air of a man who has traversed some lonely terrain of experience, of loss and gain, of nearness to death which leaves him isolated from the mass of others.”

Again, when you consider the number of eligible voters who read and/or talked about this piece, it’s not all that much of a stretch to include it with Nixon’s third-degree sweat in the first debate and the alleged Democratic skullduggery in Chicago as a factor in the “marriage” represented, for better or worse, by the Kennedy administration. Before retiring this somewhat shaky analogy, it’s hard to resist noting that the miserable marriage we’re enduring at the moment was a shotgun wedding.