|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 46

|

|

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

|

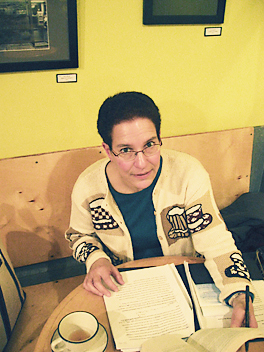

(Photo by Linda Arntzenius)

Author and translator Shelley Frisch in Small World.

|

Shelley Frisch adores coffee. Even more than the flavor and kick of the beverage itself, being surrounded by the aroma inspires her. Most afternoons, Ms. Frisch can be found at any one of Princeton’s local coffee houses — she’s particularly fond of Small World, where we met for this interview — working on her latest book. Her translation of German author Jürgen Neffe’s Einstein: A Biography was published this year and her latest work, The Secret Pulse of Time by Stefan Klein, will hit bookstores this month. As the unsung heroes of foreign literature with the potential to turn works of national acclaim into international bestsellers, translators are now beginning to be acknowledged alongside authors. The cover of Neffe’s biography also bore Ms. Frisch’s name. Here, the Jefferson Road resident, who has been a translator and writer since 1995 and just received the 2007 Modern Language Association’s Scaglione Prize for a Translation of a Scholarly Study of Literature, discusses the work that coffee makes possible.

I’ve always been interested in language and even dreamed of being a lexicographer — not a typical childhood dream, perhaps. The idea of picking apart words and identifying what makes them communicate meaning is something that I’ve thought about for many years. In fact, I wrote my first book on this, The Lure of the Linguistic, in 2004. After teaching German literature and language for over 20 years at the university level and doing occasional translations, I was approached with a book project and I thought I’d give it a try. I really quite liked it although it’s surprisingly exhausting work. People who don’t translate think it’s just a mechanical matter, as I did at first, but it’s not in the slightest.

I try to get at the literal meaning in an early draft. I go through the entire text very quickly first to get a grasp of the author’s general thought patterns, linguistic foibles, and to develop a sense of the author’s voice. I try to assume that voice and communicate the liveliness of the text. Quite frankly if the text is not as lively as it might be, I do what George Steiner in After Babel calls “betrayal upwards,” and add a little spice to it — a dash of alliteration, a pinch of sibilants, a smidgen of contrast intonation. If a paragraph repeats the word “nice” several times, I get to work on my synonyms. If a pronoun has no antecedent, I supply one. If the punctuation is misleading, I recast it. If a single paragraph expands out over several pages, I chop. A text that deserves to be translated deserves to read well in the target language.

The most challenging aspect of this work is the research each project requires. I specialize in non-fiction and spend much more time doing library research than I had ever imagined I would. Each new text I tackle entails mastering the “idiolect” of the author. Every writer has favorite expressions — some quite quirky, some enchanting, and alas, some irritating. I have also become more aware of my own idiolect, and at times make a game of putting my personal imprint on texts. After hours of tracking down the words of others, I sometimes indulge in a bit of linguistic play. I’ve made a point, for example of using the word “ensconced” in virtually every one of my translations. I also love the word “beleaguered,” and I’m very fond of alliteration. I also have to master the “lingo” of the field of inquiry. Each field has its own mode of expression, and I have had to become fluent in fields, ranging from psychology to physics, from pre-Socratic philosophy to Maroon rebellions, eunuchs and castrati, to condoms and Communism. I feel fortunate to live in Princeton, which has experts in virtually every possible field, no matter how arcane. For my recent translation of Jürgen Neffe’s Einstein biography, I am grateful to many local physicists for help with scientific terminology.

People often quite mistakenly think I’m an expert in these fields because I’ve translated books on Einstein, Kafka, and Nietzsche. Of course, by the time I’ve finished each book, I do have some expertise in the field. That’s the delight of it. I’ve always loved scholarship and writing and the joy of immersing myself in a new project with a new language.

The Secret Pulse of Time is written with a light touch, funny at times, but also thought-provoking. It takes the reader on so many different paths and synthesizes so many fields. It’s a marvelous book. As I was translating the text, I found it paradoxical to be thinking deeply about the nature of time while facing deadlines.

Typical Day

In a typical morning, I work for a couple of hours, do an hour of aerobics at home and then, with several doses of caffeine at hand, I get back to work. In the afternoon, I print out a set of pages and bring them to Small World or, if the weather is fine, I might cycle over to Barnes & Noble (or Borders, a slightly more dangerous ride) and scribble on those pages before bringing them back to my computer. Computers are indispensable for my work but I like to use printouts and see the material with fresh eyes.

I’m working on several projects right now: a heart-rending story about several girls who lived in one room, Room 28, in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Amazingly, they are still alive and meet every year, usually in Prague. They kept diaries while they were there. The Girls of Room 28, to be published by Schocken Books in 2008, is a very poignant book. At the same time, I’m working on a short biography of an early 20th-century Jewish condom manufacturer named Julius Fromm who was hounded out of his business in the early 1930s. Hermann Goering made a present of the condom factory to his godmother, a sign of the legal dysfunction of the day. Even after the war, Fromm was not able to reclaim his business. I now know more about condoms and their manufacture than I ever imagined I would. But hey, after eunuchs and castrati, I am prepared for any subject.

Besides these translations, I’m also writing a biography of Erika Mann, Thomas Mann’s oldest daughter. In addition to being one of the most outspoken lecturers in the United States, she was one of the first in Germany to recognize and raise the alarm about Hitler and his plans. She took him seriously from day one but was ridiculed for it. People called her “Cassandra” for her prophecies of doom and gloom.

I grew up in New York City and was the first of my family to go to college, at the age of 16. When I was 21, after college and a year in Germany on an exchange scholarship, I came to Princeton for graduate school and a Ph.D. After that I taught at Columbia University and Haverford College for many years. My husband Markus Wiener, who is a German native, runs a small press for which our sons Aaron, 22, and Noah, 20, have been involved since they were in diapers. Both of them have copy-edited manuscripts. Aaron has compiled catalog copy and Noah designs most of the book covers. It’s a family business.