|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 41

|

|

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 41

|

|

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

|

|

Books, books, and more books. It’s that time of year again.

Another Friends of the Princeton Public Library Book Sale is looming, and the unprecedented volume of this year’s stock of donations is challenging the storage capacities of the new library building. Beginning next weekend, I will be up to my ears in novels, histories, biographies, cook books, art books, and all manner of quaint and curious volumes. What do I mean will be? I’m always up to my ears in books. Every day throughout the year there are masses of donations to plow through. Day after day it’s up to me to stock the shelves for the library’s ongoing sale while socking thousands away for the fall spectacular. Books seek me out. I don’t drive a car, I drive a bookmobile.

So, how does one come to play this role? How does one become a Book Person, as opposed to a Math Person or a Science Person?

The facts suggest that this Book Person’s fate was sealed by age six, if not before. Born into a bookish family, the father a scholar, the mother a writer, the family typewriter always clattering away, the BP in embryo is hopeless at math and science and has no common spatial sense (“That child doesn’t know left from right,” his grandmother says), but when he opens a dictionary, he’s right at home, and he’s a whiz at Authors. Thanks to his fondness for that card game, he can tell you who wrote what by the time he’s in first grade. His idols, pre-Stan-Musial and Sonny Rollins, are Hawthorne, Melville, Twain, Dickens, and Shakespeare, literary movie stars staring out at him from each card, their eyes shining, a touch of color in their cheeks.

The definitive moment comes, however, when the boy’s parents introduce him to Classic Comics. Did they know what they were doing? Did they know they were exposing him to role models that would change the course of his life? Did they know they were creating a mystique from which nothing sensible or practical could distract him? Because his father did not merely give him these comics, he conjured them. He would say “Look under the cushion on the sofa!” or “Look under the rug!” and then with a flourish and a cry of “Abracadabra!” presto! Under the cushion, the child would find The Three Musketeers, under the rug, A Tale of Two Cities. No wonder the BP’s old Classic Comics still glow with a touch of magic. Before long, the eight-year-old is superficially conversant with Moby Dick, Huckleberry Finn, The Last of the Mohicans, and, even more important to the shaping of his fate, he’s become intimate with the life stories of the authors included at the back of every issue. Soon he’s making up his own Classic Comics about knights and rogues, complete with brief biographies of himself under a sketch of the author in bearded middle-age (“He died peacefully in Rome in 1990”). Is it any wonder that he grabs the family typewriter at age ten and begins making up a novel based on his travel fantasies? And is it any wonder that he ends up writing books and book reviews and directing book sales?

The Tome

Last week, thanks to the ever-growing DVD collection at the Princeton Public Library, my wife and I watched the 1933 French version of Les Miserables. The film is almost five hours long and seldom dull. But Jean Valjean, unforgettably played by the gargantuan Harry Bauer, was no match for the handsome hero I knew in my favorite Classic Comic (No. 9), and neither the arch stalker Inspector Javert nor the hideously evil Msr. and Mme.Thenardier were as vile as my comicbook image of them. In case I doubted my memory, I still have the item in question; my parents had it bound with the rest of the first 20 issues into a single massive volume, which they presented to me on the occasion of my eighth birthday. All I have to do is bury my face in the time-mellowed pages of that tome and I’m back there again; it’s my version of Marcel’s madeleines. The heady scent preserved between those solid, durable covers is the very atmosphere of cozy childhood hours.

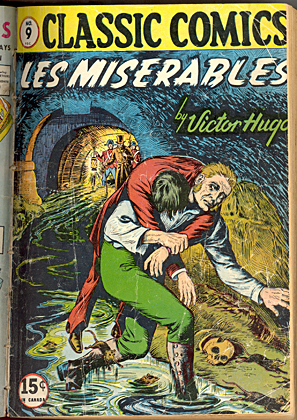

When I went back to the big bound volume after seeing director Raymond Bernard’s Les Miserables, I was struck by the power of the imagery all through the first 20 issues, regardless of the illustrator. It may seem foolish to talk about the impact of pictures that are surely tame compared to what eight-year-olds are exposed to in 2007, but these depictions of adult texts, while they may fall short of the standards of the best work in the graphic novel revival, are worth examining. I read my share of Superman, Batman and Robin, and Captain Marvel, too, but I remember nothing in them as intense as the cover of Les Miserables, which shows Jean Valjean lunging through the sewers of Paris with his adopted daughter’s wounded lover on his back and filth and rats and human skulls at his feet. It was on the title page of Victor Hugo’s creation, however, that the artist, Rolland H. Livingstone, really outdid himself. You see Jean Valjean in rags, staff in hand, pack on his back, head turned toward the immense spectral presence filling the blue sky behind him. Spiralling into a brown miasma from the smokestacks of factories, arms raised, talons coiled, yellow eyes glaring, teeth bared, is the simian nightmare of the relentless Javert. Do such things stick in the mind of a preadolescent kid? You bet they do.

I must have been no more than seven when my father conjured up Classic Comics No. 1, The Three Musketeers. Imagine the effect of the concluding image on a child that age. A masked executioner is about to behead a kneeling woman, her long blonde hair streaming down over her face, her hands clasped behind her back. The accompanying text reads: “Then, from the other bank. they see the executioner slowly raise both his arms. A moonbeam falls upon the blade of the large sword. THE TWO ARMS FALL WITH A SUDDEN FORCE. They hear the cry of the victim, then a truncated mass sinks beneath the blow” (all the words are actually in capital letters, but the ones I capped here are set larger and in bold-face as well). My guess is that, being old enough to read, I made right for my old pal the dictionary to look up “truncated.” (It was also cheering for a math-challenged child to read in the bio that Msr. Dumas “never got beyond the multiplication tables”).

I have no way of estimating the popularity of these comics, which were sold at first in gift boxes of five (for a mere 50 cents), but my guess is that they had an appreciable influence on kids who grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, being also widely available along with the usual superhero and funny animal comics in drug stores or newsstands. The people putting each number together eventually used the back matter to spread the message for a nation at war. While the first issues carried only the author’s biography, by No. 4 (The Last of the Mohicans), the bio of New Jersey’s native son, James Fenimore Cooper was followed by a boxed ad urging parents to buy war bonds and stamps. At the end of No. 5 (Moby Dick), references to patriotism were worked into the author’s biography, where one of Herman Melville’s Civil War poems was quoted (“Over and over, again and again/Must the fight for the Right be fought?”); the last page featured an illustrated version of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Concord Hymn,” (“Spirit, that made these heroes dare to die”) followed by a drawing of the Stars and Stripes. From that number on there were anecdotes about war heroes in almost every issue, along with illustrated poetry that was not always there for patriotic purposes. Just now I was surprised to find Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” at the back of No. 10 (Robinson Crusoe), where wartime children could read that the world “hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,/Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.”

As for the age range the creators of these precursors to the graphic novel had in mind, it was surely not for under tens but for kids in grades five to nine. A quick look online shows that contemporary versions like Graphic Classics and Saddleback’s Illustrated Classics have apparently spawned some debate about students who might be reading them instead of the true texts. When my father was teaching Crime and Punishment in a freshman survey course and the word got round that students had found a way to avoid reading the real thing, he consulted the comicbook version. By then the name had been changed to Classics Illustrated. Never mind. As far as I was concerned, my father, the austere magician, was sitting there engrossed in a Classic Comic and making notes.

This year’s book sale, by the way, will feature a table of volumes from the eclectic library of the late Borough Mayor Joseph O’Neill. His collection of vintage Donald Duck comics, sad to say, will not be among them.