|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 41

|

|

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 41

|

|

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

|

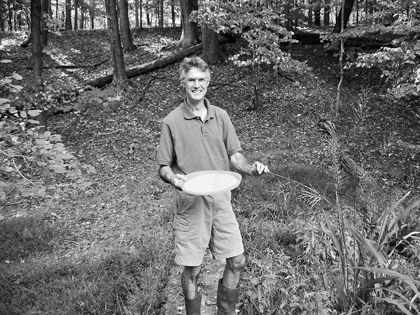

(Photo by Linda Arntzenius)

“Education is a part of everything that I do; my role is as a catalyst bringing people together to create something that will sustain itself.”

— Steve Hiltner, Natural Resources Manager, Friends of Princeton Open Space |

Steve Hiltner struggles with the term “natural.” As the Natural Resources Manager for Friends of Princeton Open Space (FOPOS) since 2005, he has pondered the term that, he said, many people mistakenly equate with “green.” Those healthy looking green plants may well be non-native invasive species that do little good for local birds, insects, and other wildlife. A casual observer may mistake for “natural” a declining marshland strangled by the rampant giant reed, phragmites. “I could name 30 different invasive species that have been introduced by human beings,” he said. “They present an immense challenge. Japanese Stilt Grass, for example, is an annual that benefits no wildlife, is in every square foot of our preserves taking up valuable space that could be occupied by a native species that feeds birds, insects, and other animals.”

You may have seen Mr. Hiltner in the woods, collecting wild rice seeds at the Mountain Lakes Preserve, or battling invasives such as purple loosestrife, bindweed, nut sedge, multiflora rose, or phragmites, the bane of East coast marshlands, including the Meadowlands marsh ecosystem.

Also a member of the Princeton Environmental Commission and a consultant for the Charles H. Rogers Wildlife Refuge, Mr. Hiltner focuses on habitat restoration and environmental education. His mission is to inform the Princeton community about the beauty of the local environment. To this end, he works with Princeton Regional Schools on projects such as the wetland laboratory at the high school being used for the study of horticulture and environmental science, as part of his public outreach work for FPOS. He is currently helping students at the high school set up a plan for recycling paper and soda cans, a measure that began with first grade teacher Kirsten Fenton, the science coordinator at Riverside School. “Institutions have many choices for recycling but the bottom line is that everyone has to be involved because everyone is part of the problem and therefore has to be part of the solution. Usually it’s a many step process involving everyone from the superintendent to students who will run this program.”

Mr. Hiltner grew up in southeast Wisconsin close to the Yerkes Observatory, which was landscaped by the Olmsted firm of Central Park fame. “I grew up in a designed landscape where I could explore and so I became interested in identifying plants and organic gardening as a high schooler.” While his interest in the environment grew, he made a living as a freelance jazz musician and musical director for a 20-year period from the mid-seventies to the mid-nineties, with ten of those spent as directing an 8-piece ensemble.

He followed a 1983 bachelor’s in cultural botany from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, with an MPH in Water Quality in 1987 from the University‘s School of Public Health.

He now lives on Harrison Street with his Argentinian wife, Gabriela Nouzeilles, and two daughters. Sofia is 12 and a 7th grader at John Witherspoon Middle School. Anna is 7 and a second grader at Littlebrook. The couple met in an Ann Arbor, Michigan, jazz club, where he was performing.

When his wife got a faculty position at Duke University, the couple moved to Durham, N.C., where Mr. Hiltner founded the Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association in 1999. In 2001, he was named Urban Conservationist of the Year by the Durham Soil & Water Conservation District. In 2002 he won the Headwaters Group Sierra Club environmentalist award and in 2003 he won the Garden Crusader, First Place Beautification award from the Gardener’s Supply Company.

After relocating to Princeton, Mr. Hiltner immediately began volunteering with the Friends of Princeton Open Space, the group that has helped preserve local natural treasures such as the Institute Woods, the Mountain Lakes Preserve, and Tusculum. When the group received a grant from Washington Audubon for assessment purpose, Mr. Hiltner was a “natural” choice for the task, having carried out a similar assessment for the Borough’s Harrison Street Park.

Project Driven

Steve Hiltner owns to being “project driven.” He is happy to see progress almost every day. “I’ve learned to be patient and persistent. In Princeton, people are more open to ideas than in other places I’ve lived. Everywhere there is inertia toward change, but in Princeton there is less of that.” Through a nature journal (www.princetonnaturenotes.blogspot.com), he acquaints Princetonians of their local plant heritage and of efforts to restore native diversity and beauty. His Princeton Nature Blog on the FOPOS website (www.fopos.org) has advice on natural plantings, native plant workshops, and news about volunteer clean ups on Princeton’s preserves and parks. There, for example, visitors can find out when and where the cutleaf coneflower is in bloom, when to see wild rice at its best in the Rogers Wildlife Refuge (the birding mecca that includes several acres of marsh between the Stony Brook and the Institute Woods), or when to see Indian Grass and Big Bluestem, mainstays of midwestern tallgrass prairies that also flourish in the east (the prairie at the entrance to Bowman’s Hill Wildflower Preserve along the Delaware River).

Mr. Hiltner also holds a series of native plant workshop, co-sponsored by FOPOS and the Whole Earth Center. [For more information call the Whole Earth Center at (609) 924-7429.] At a recent workshop, he described seed gathering and plant inventory initiatives for the coming year, before leading participants on a tour of nearly 100 native species.

“When all the right factors are in place: auspicious hydrology and sun levels, desired plants dominating, and none of the more aggressive invasives threatening, wetland plantings are low maintenance. But without well-timed intervention and quick response to invasives, they can start to look weedy and serve to reinforce people’s worst stereotypes. Even a robust wetland like the Rogers Refuge marsh in town needs someone to worry about it, to intervene when the phragmites starts getting a foothold, to stop by to make sure the pump hasn’t broken down.”

“I definitely prefer landscapes that can take care of themselves. Getting them to that point is the challenge. There’s just not enough hours in the day.”