|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 16

|

|

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

|

|

I look in vain for the poet I describe ….Time and nature yield us many gifts but not yet the timely man, the new religion, the reconciler, whom all things await ….We have yet had no genius in America, with tyrannous eye, which knew the value of our incomparable materials.Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Poet” (1844)

If Emerson were the master of ceremonies teasing his audience with those words, now would come the fanfare, the curtains would part, and Walt Whitman would step onto the stage in the floodlit arena of the ages. But the star of this show isn’t the lap-robed sage of Camden, N.J., in his rocking chair; it’s the 37-year-old roughneck from Brooklyn pictured in the first 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass eyeing posterity’s full house as he prepares to rock us out of our seats and into the aisles.

Such is the wonder of Whitman. If you want to spin outlandish analogies, go ahead, picture him as a bare-chested, sweating rock and roll hero chanting his incredible word-music to an arena packed with arm-waving fans before stripping the rest of his clothes off to close the show with a headfirst dive into the mosh pit. Go ahead, roll the dice, shoot from the hip, call the shots, turn the volume up till the amps roar and howl — with Whitman, anything goes, he’s always right there, fresh and fierce and never less outrageous than he is in 1855 when he reaches out and brings you in, like it or not: “You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,/ And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart,/And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet.”

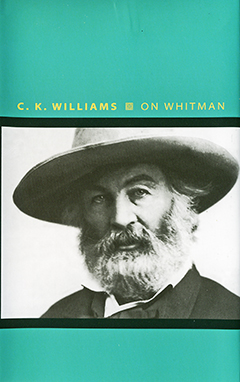

C.K. Williams on Whitman

The reality is that there’s finally too much Whitman to take in, too many lists, too many litanies, whether it’s in this first incarnation of Leaves of Grass, or the Death Bed Edition. Best not to take him straight, all in one gulp. Best to have the right person leading the way, digging down to the essence of the work with enlightened passion as poet C.K. Williams does in his new book, On Whitman (Princeton University Press $19.95). He knows you can’t muse shyly behind the scenes when your goal is not merely to show how it feels to read the poetry, but how it feels to be the poet:

“But how wildly exciting, how really exalting it must have been to him when his poetry first offered him a way to see and record so much — it can feel like everything. Just reading it, the brilliance of the moments of inspiration can seem like raw synaptic explosions, like flashbulbs going off in the brain, in the mind: pop, pop, pop. The images, the ideas, the visions, the insights, the proclamations, the stacks of brilliant verbal conjunctions, the musical inventiveness and uniqueness: one after the other, again and again, in a form that reveals them naked, unmodulated, undimmed by any apparent resort to the traditional resources of poetic artfulness.”

Williams isn’t talking about some distant realm of verse. He’s talking about electricity. Those popping flashbulbs may be what triggered my rock and roll analogy, the vulgar glamour of the star in floodlit performance. The flashbulbs are popping again when Williams attempts to comprehend how a mere mortal with modest journalistic skills could have morphed into this word-drunk demigod: “It’s as though his actual physical brain went through some incredible mutation, as though — a little science-fiction, why not? — aliens had transported him up to their spaceship, and put him down again with a new mind, a new poetry apparatus. It is really that crazy.”

Crazy, yes, why not? Forget academic decorum. Go at it full-tilt as D.H. Lawrence does when he riffs on Whitman in Studies in Classic American Literature. But Williams is not preaching; he’s trying to put the constellations of Whitman into some kind of fathomable alignment.

Emerson

On July 21,1855, when Emerson wrote to Whitman after reading the first edition of Leaves of Grass, he was clearly stunned, overjoyed, ecstatic, if not also appalled that the genius with the “tyrannous eye” he’d conjured up in “The Poet” had come to life. How could he not be excited? The prodigy who created “this wonderful gift” had escaped from his own imagination. When Emerson writes “I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy,” he also means “as my great power makes me happy.” Next comes a line that must have delighted Whitman, a line he could have written: “I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion.”

Whitman’s preface to the 1855 Leaves is “The Poet” writ large. It’s Whitman the one-man band jamming his heart out, full-speed ahead, but as C.K. Williams makes clear, the qualities and responsibilities of “the greatest poet” that Whitman is pouring forth “aren’t like anything in even the most fantastic primer for poets.” The rhetorical force in “The Poet” is contained. In the prologue the only time Whitman takes time to catch his breath may be in the ellipses that score this prose fantasia like some improvised form of musical notation: “The American bards shall be marked for generosity and affection and for encouraging competitors …. They shall be kosmos … without monopoly or secrecy … glad to pass any thing to any one … hungry for equals night and day.”

That relatively tame example of Whitman’s unbridled prose segues nicely into the masterwork of an American bard who is Whitman’s only equal and who knew a thing or two about kosmos — and who almost undoubtedly inspired this “competitor” four years before Leaves of Grass ever saw the light.

Melville

I’d like to think that D.H. Lawrence’s motive for closing his book on American literature with chapters on Moby-Dick and Walt Whitman can be read into a statement made by Lewis Mumford five years later in his 1929 biography, Herman Melville, in which he declares that Melville “shares with Walt Whitman … the distinction of being the greatest imaginative writer that America has produced” and that “his epic, Moby-Dick, is one of the supreme poetic monuments of the English language.”

While there’s no doubt that Emerson helped bring Whitman into full flower, there are flights of fancy all through Moby Dick that would have electrified him. Whether he felt intimidated or liberated by Melville’s mastery, he’d have recognized a very great competitor. Writing in the Brooklyn Eagle, he’d given positive notices to both Typee (“As a book to hold in one’s hand and pore dreamily over of a summer’s day, it is unsurpassed”) and Omoo (“One can revel in such richly good-natured style”). If he liked Melville Light, imagine how responsive the author of “I Sing the Body Electric” or “Children of Adam” would be to chapters like “A Squeeze of the Hand” where the crew of the Pequod sets to squeezing lumps of sperm into fluid: “A sweet and unctuous duty! No wonder that in old times sperm was such a favorite cosmetic. Such a clearer! such a sweetener! such a softener! such a delicious mollifier! After having my hand in it only a few minutes, my fingers felt like eels, and began, as it were, to serpentine and spiralize.”

And Melville goes on and brilliantly on, with “generosity and affection,” much as Whitman would, but with a playfuness seldom found in Leaves of Grass: “Squeeze! squeeze! squeeze! all the morning long; I squeezed that sperm till I myself almost melted into it; I squeezed that sperm till a strange sort of insanity came over me; and I found myself unwittingly squeezing my co-laborers’ hands in it, mistaking their hands for the gentle globules. Such an abounding, affectionate, friendly, loving feeling did this avocation beget; that at last I was continually squeezing their hands, and looking into their eyes sentimentally; as much as to say, — Oh! my dear fellow beings, why should we longer cherish any social acerbities, or know the slightest ill-humor or envy! Come: let us squeeze hands all round; nay, let us all squeeze ourselves into each other; let us squeeze ourselves universally into the very milk and sperm of kindness.”

Pretty Whitmanesque, is it not, four years before he came out of his Brooklyn closet. You know Walt would have related to Ishmael sitting there cross-legged on the deck in a spermy daze, sniffing “that uncontaminated aroma” like living in a “musky meadow” amid notions of universal brotherhood. You could say the difference is that Whitman put less distance between himself and his persona than Melville did between himself and Ishmael. Still, given the likelihood that Whitman got his hands on Moby-Dick at some point during the composition of Leaves of Grass, might not he have admired the wonderfully elastic and funny and intimate voice Melville was able to create for Ishmael? And might not that have influenced his own approach to the creation of the Walt Whitman who has captivated readers with such inspired, hands-on immediacy for the past 155 years?

Although C.K. William’s National Poetry Month reading at the Princeton Public Library took place Tuesday night of this week, he will be at Labyrinth Books next month, on May 4 at 5:30 p.m., reading from On Whitman and as well as from his own new collection, Wait.