|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 17

|

|

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

|

|

Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied? — come, children, let us shut up the box and the puppets, for our play is played out.William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair

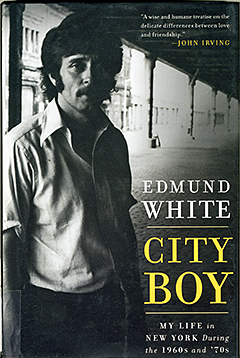

I thought of Thackeray’s famous coda of farewell as I finished Edmund White’s gossipy, unapologetically promiscuous book of revelations, City Boy: My Life in New York During the 1960s and ’70s (Bloomsbury 2009). Promiscuity is everywhere in White’s Manhattan; it’s not just in the free flow of sex; it’s in the style and sweep of the narrative, and it’s in the mixture of urban intensity and rampant ambition that, according to the author, “consumed” New York with all its “improvised and transient … arrangements.” As White rings down the curtain on his Vanity Fair, he imagines a “theater where one play after another, decade after decade, occupies the stage and the dressing rooms,” each play “the biggest possible deal” until it vanishes, the actors “forgotten,” the plays “just battered scripts showing coffee stains and missing pages.”

Except that White’s New York is not a box of puppets that can be shut up, nor a play that is played out. “Nothing lasts in New York” — except New York itself, where “the life that is lived … is as intense as it gets.”

An Unforgettable Friendship

“Love is a source of anxiety until it is a source of boredom; only friendship feeds the spirit.” White makes this observation midway through City Boy in reference to his cherished friendship with the scholar, critic, and Rutgers English professor David Kalstone, who died of HIV/AIDs in 1986 at the age of 53. To White, their friendship was “a strange tree to grow in New York, where so many relationships of all types were corrupted by self-interest. The idea of having important friends who could impress others and predispose them in your favor was a typically New York notion …. My friendship with David was disinterested — neither of us had anything to gain from knowing each other — or nearly so … neither of us was ever using the other.” The relationship was for all purposes “sexless and ultimately satisfying” once David “recast his love into … an unforgettable and inimitable friendship, which ended only with his early death.”

Here I should mention that I was a student of David Kalstone’s in the graduate English program at Rutgers. White’s “subtle and gentle” friend with the “sweet, wise smile” was my dissertation advisor. The only professor I felt comfortable calling by his first name, David always seemed to have a cold, blew his nose with gusto, wore unbecoming glasses with thick lenses, and was sartorially challenged (rumpled, inexpensive clothes, clashing colors, worn-down shoes — style was not his thing). Except for his booming laugh, he seemed to fit the stereotype of the absentminded, unworldly academic. Then one day the glasses were no more, the clothes looked expensive, the colors were subtle, the shoes were classy, the rumpled aspect was a thing of the past, and rumor had it that he was spending his summers in Venice. The first hints of the transformation had come when he moved from an apartment in New Brunswick’s nondescript Bishop Towers to Manhattan’s Chelsea district, where he lived, according to White, “in a floor-through of a brownstone in a lovely disorder of half-filled teacups and freshly opened ‘little’ magazines, of ballet programs and long telephone cords. of cast-aside Missoni sweater vests and extra pairs of reading glasses.”

Graduate students have a tendency to gossip and speculate about the private lives of their professors, but not even the wildest fantasy could match White’s account of David’s “extravagant summers in Venice, where he would rent a whole floor in a palazzo.” It’s like something out of Balzac: Professor Kalstone, the mild-mannered scholar who “mounted a campaign to conquer Venetian society,” whose “conquests were effected at the Cipriani pool” and included Peggy Guggenheim, to whom he would read from Henry James’s Venetian novel, The Wings of the Dove. White’s gift for deftly and succinctly sketching the many celebrities filling his busy, crowded canvas is particularly evident in his portrayal of Guggenheim, who would go to gallery openings wearing “one abstract earring and one surrealist earring to show — in her loopy way — how impartial she was. Now in Venice she hung all her earrings on the metal bedstead that had been designed for her by Alexander Calder.” She also had “the last private gondola in Venice,” but was too cheap “to hire a normal gondolier who belonged to the union.” One summer “David helped her line up a gondolier who’d conducted funeral boats to San Michele. If, after boarding, Peggy didn’t give him a specific goal, he’d automatically start heading for the funeral island and singing traditional dirges.”

While most of the individuals inhabiting White’s Vanity Fair are broadly sketched in similarly anecdotal terms, David Kalstone is always right there, never treated solemnly or superficially, never explicitly lamented, but funnily, affectionately returned to again and again: David, who while “usually so fearful and unphysical, knew just how to step onto the boat without slipping,” to “stand all the way across [the Grand Canal] without staggering,” David “with his face tanned and his hair silvered by the sun, wearing his azure-blue silk shirt and hand-sewn beige silk-and-wool trousers and black gondolier slippers and gold seal ring emblazoned with the Venetian lion.” And still the scholar, who, whenever he ventured out would take “a demanding book with him — a new study of Spenser, say, or Ashbery’s Three Poems.” Although he was not a poet himself, the field closest to his heart was poetry, not only in his analysis of texts (as in his 1977 book, Five Temperaments) but in his delineation of poet-to-poet relationships, the subject of the posthumously published Becoming a Poet (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 1989).

New York

In my focus on David Kalstone, I’ve inadvertently slighted the scope of Edmund White’s vision of a New York “obsessed with the hierarchy of the arts and the idea of the Pure,” where gay New Yorkers had to “separate out friendship, love, and sex,” with friendship given “the starring role.” As for stars, City Boy’s cast includes, in addition to Peggy Guggenheim and numerous others, Susan Sontag, Lillian Hellman, Jasper Johns, Vladimir Nabokov, and the Killer Bs, Borges, Burroughs, Balanchine, and Elizabeth Bishop.

I have to admit I was hooked the minute I read that White’s first residence in the city was “the Sixty-third Street YMCA, which in those days was pretty much a fairy palace … a mock-Moorish fantasy of tile work and low ceilings, as well as a giant swimming pool where Tennessee Williams was often sighted.” That Moorish fantasy also housed McBurney School where I spent ninth grade. Little did I know. And little did I know that the Stonewall uprising was set off, according to City Boy, not by “those crewnecked white boys in the Hamptons and the Pines” but by “the black kids and Puerto Rican transvestites who came down to the Village on the subway (the ‘A-trainers’), and who were jumpy because of the extreme heat” and “worked up because Judy Garland had just died of an overdose and was lying in state at the Riverside Memorial Chapel.”

The New York in City Boy may be the one people refer to in 2010 in terms of the “bad old days,” but for writers and artists, it was “crucial” to be there “when it was dangerous and edgy and cheap enough to play host to young, penniless artists,” a Vanity Fair where life, however you live it, “is as intense as it gets.”

Both City Boy and Becoming a Poet are available at the Princeton Public Library. Edmund White teaches creative writing at Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts.