|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 45

|

|

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

|

|

Are you the new person drawn toward me? To begin with, take warning — I am surely far different from what you suppose.Walt Whitman

It was once the case, according to one folktale that “vampires were as common as leaves of grass.”from a Romanian journal of folklore

Although he spent several years researching European folklore and mythological accounts of vampires before writing Dracula, Bram Stoker (1847-1912) never actually visited Transylvania. He preferred the U.S.A., where in April 1884 and December 1887, he made special trips to Camden, N.J., to see Walt Whitman (1819-1892), the man to whom he’d written in 1872, suggesting that Whitman could be if he wished, “father, and brother and wife to his soul.”

Harold Bloom amplified the same idea in his introduction to the 150th anniversary edition of Leaves of Grass: “If you are American, then Walt Whitman is your imaginative father and mother.”

So far, so good. But what if our imaginative mother and father was also “the model for the character of Dracula”? I’m still trying to get my head around that idea, which is being circulated online and even in the same Whitman wikipedia entry that quotes Bloom. Somehow I don’t think Stoker would agree. If Whitman had been alive in 1897 when Dracula was published, I doubt that he’d have received a presentation copy inscribed to that effect. The determining phrase is in Stoker’s notes for the novel, where he suggests that Dracula represents the “quintessential male” — the assumption by some authorities being that since Whitman also represented “quintessential male” to Stoker, Dracula was inspired not by Vlad the Impaler but by the Good Gray Poet.

A Passionate Letter

No doubt about it, a Stoker-Whitman connection does exist. The two men did meet and did correspond, but there’s nothing in what I’ve seen of the correspondence to encourage the notion that the cosmically genial poet and gay icon might have essential or even quintessential qualities in common with a Transylvanian vampire Stoker compares to “a filthy leech” gorged with blood who when enraged has a “red light” in his eyes “as if the flames of hell-fire blazed behind them.” If you work at it you can probably find a homoerotic edge in Dracula’s rage, set off when he catches three female vampires about to sink their teeth into his guest and prisoner, Jonathan Harker. As he hurls the women aside, the Count shouts, “Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me!” He then promises them “that when I am done with him, you can kiss him at your will.” As a consolation prize he gives them the body of a child to “kiss.” Not exactly what you’d call a Whitmanesque situation — at least not unless you take Whitman’s rhetoric of appetite literally.

Online publicizers of the Whitman/Dracula connection point to the verse “Trickle, Drops” from the Calamus section of Leaves of Grass (“O drops of me! trickle, slow drops,/Candid from me falling — drip, bleeding drops.../Glow upon all I have written, or shall write, bleeding drops”).

One of Stoker’s biographers, Barbara Belford, stresses the impact such a vision might have had (“Similar images vividly explode in Dracula”), but this was only one seed among a multitude disseminated by a poet singing “Of life immense in passion, pulse, and power/...for freest action form’d, under the laws divine.” In fact, the 25-year-old Stoker was so devoted to and intimidated by Whitman that it took him four years to get up the nerve to send the aforementioned letter, which is quoted in full in Horace Traubel’s With Walt Whitman in Camden. Brash, ardent, and frankly familiar, the letter is a classic outpouring from a disciple at once shyly, slyly, and passionately importuning — or you could say, “coming on to” — the master by all but daring him to “put the letter in the fire” before reading it, and then coyly suggesting that such an act would be unworthy of “a man who can write, as you have written, the most candid [the same word used in “Trickle, Drops”] words that ever fell from the lips of mortal man — a man to whose candor Rousseau’s Confessions is reticence,” a man who “can have no fear for his own strength.”

The most striking and provocative part of the letter comes when Stoker physically introduces himself to Whitman: “I am six feet two inches high and twelve stone weight naked and used to be forty-one or forty-two inches round the chest. I am ugly but strong and determined and have a large bump over my eyebrows. I have a heavy jaw and a big mouth and thick lips — sensitive nostrils — a snubnose and straight hair. I am equal in temper and cool in disposition and have a large amount of self control and am naturally secretive to the world. I take a delight in letting people I don’t like — people of mean or cruel or sneaking or cowardly disposition — see the worst side of me.”

Impressed, Whitman tells Traubel it’s “a mighty graphic picture,” which shows him Stoker “not as in a glass darkly but as in the broad day lightly.” Read Stoker’s description of Count Dracula and you’ll notice terms similar to those he used to describe himself to Whitman (“strong,” “heavy,” “arched nostrils,” “eyebrows...very massive, almost meeting over the nose,” “astonishing vitality”).

So maybe Stoker modeled Dracula not on Whitman but on himself. No wonder, then, that Belford titled her 2002 biography Bram Stoker and the Man Who Was Dracula.

The Vampire Craze

At the risk of seeming chronologically irrelevant, I’ve been writing this column on October 31, knowing that by the time it appears, Halloween and October will be old news. It seems, however (and no wonder), that the Undead will never be dated. On June 2, 2003, Stephenie Meyer had a dream about a vampire who was in love with her, wrote a book inspired by the dream called Twilight, and the rest, as they say, is history. The Twilight series is a publishing sensation, Meyer was named USA Today’s “Author of the Year” in 2008, having sold over 29 million books.

It was due to the current rage for vampires that I picked up a paperback of Dracula the other day and began reading it again for the first time since I was 17. I’ve also watched some Dracula movies, including Francis Ford Coppola’s tumultuous travesty, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which my wife and I gave up on after maybe ten gaudy, overblown minutes. We were joking that the guy playing Dracula’s demented victim Renfield looked like Tom Waits (well, hey, it was Tom Waits). That budget-busting mess made me appreciate the likeably unpretentious Blood of Dracula, directed by my late father-in-law Herbert L. Strock and shown twice this past week as part of AMC’s Halloween Fear Fest. This little American International quickie (most of Herb’s films were quickies) features a Bill Haley-era number called “Puppy Love” and an evil science teacher who looks like Ayn Rand and uses a Transylvanian amulet to hypnotize a perfectly nice if somewhat temperamental girl into feasting on her fellow students.

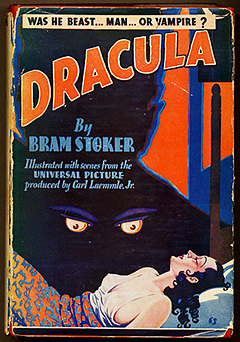

On Halloween night, after the last of the trick or treaters had gone, we watched the one and only Universal Pictures Dracula directed by Tod Browning with Bela Lugosi as the definitive Count (who, it’s safe to say, will never be mistaken for Walt Whitman), and with bug-eyed Dwight Frye stealing the movie as the original Renfield, that crawling, panting gourmet of the unspeakable. The 75th Anniversary DVD, which contains special features on the Dracula phenomenon and Bela Lugosi, is available at the Princeton Public Library, as are copies of the novel, including Transylvanian-born Leonard Wolf’s The Annotated Dracula (1975). A new annotated edition edited by Leslie S. Klinger was published last year by Norton.

The Book

Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Dracula is developed through journal entries and letters. Stoker’s style can be both subtle and florid. The journey that takes Jonathan Harker to Dracula’s castle is mined with hints of the horrors to come. Accounts of seemingly benign scenes in nature contain “a bewildering mass of fruit blossom,” a road that is “losing itself” or is “shut out by the straggling ends of pine woods” that “run down the hillsides like tongues of flame.” There are “jagged rocks and pointed crags,” “great masses of greyness” and “ghost-like clouds,” so that even before things become openly awful, Stoker is subliminally unsetting you. A few pages after observing the metaphorical red tongues of the pine woods, Harker runs into wolves with “white teeth and lolling red tongues.” Stoker then puts his fear cards on the table as the wolves form “a living ring of terror.” You can feel Poe’s presence in elements like the “deep, dark-looking pond,” and there are allusions to Hamlet, the Arabian Nights, and Coleridge, whose Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Dracula in Camden?

I’m still trying to imagine Whitman, the “quintessential man,” as the model for the dread Count. I suppose that the poet who admits “I am he who knew what it was to be evil” is capable of darker seductions. He pulls us in often enough, whispers in our ears, gives us his beard to tug, confesses to being “wayward, vain, greedy, shallow, sly, cowardly, malignant;/The wolf, the snake, the hog, not wanting” in him. If we like, we can even imagine him pulling himself out of his rocking chair and crawling — as Dracula crawls, lizard-like — along the wall of his Camden “castle” on Mickle Street. But no way is he merely the model for Dracula. He’s too large. He subsumes good and evil into poetry. So there he sits, that terrifying figure, with his big hat and long white beard while the victims his verse has intoxicated and seduced play at his feet like the neighborhood children, in his thrall, lured into the presence from all corners of the world to offer themselves in tribute. No wolves are howling — maybe a few stray New Jersey mutts — and the old poet looks more like Santa Claus than Dracula. Ultimately the truth prevails, which is that Whitman’s Leaves form a universe large enough to contain armies of vampires, and that the “simple, separate Person” singing of “Life immense” seeded the creation of one of this culture’s most hallowed and enduring tales.